Air transport today – whether civilian or military – is a complex, seamless web of people, machinery, locations and infrastructure. We take it for granted that we can ship anything anywhere in the world within a day or two, provided only that it can be broken down into loads that will fit onto an aircraft.

It wasn’t always so easy.

World War II was the catalyst in developing our modern air infrastructure. During the war huge networks of intercontinental air travel were developed: new methods of freight handling and mass passenger transport were devised: and the experience gained by tens of thousands of service personnel formed the foundation for the incredible expansion of aviation after the war. Its effects are with us to this day.

The United States was unquestionably the world leader in these developments. The Air Transport Command (ATC) was established in 1942, drawing most of the leaders of US airlines and many of their pilots, mechanics and other personnel into uniform. The ATC set up immense air routes across the Atlantic and Pacific to ferry aircraft, convey urgent passengers and freight, evacuate seriously wounded personnel for treatment in rear-area hospitals, and a host of other purposes. After the war it would conduct the Berlin Airlift and become the Military Air Transport Service. Today known as the Air Mobility Command of the US Air Force (USAF), its mission continues.

The single most challenging, demanding and difficult task of ATC during World War II was to supply the armies of Chiang Kai-Shek in China. Japan had occupied almost all of the China coast, as well as Burma. Overland access was impossible to begin with. In order to supply the Chinese armies, the small but highly effective air element commanded by General Chennault (known to history as the Flying Tigers) and, in time, the US Army Air Force’s B-29 bombers, an air bridge had to be established between India and China.

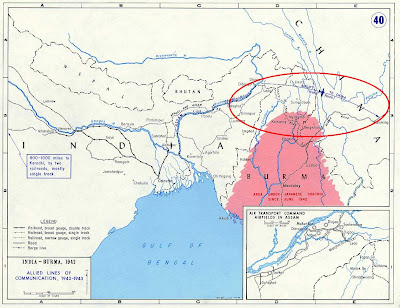

The first problem was getting aircraft to India. They flew the so-called South Atlantic Air Route, flying from Miami in Florida, via Trinidad in the Caribbean, to the port of Natal on Brazil’s Atlantic coast. From there they made the long flight across the South Atlantic Ocean to Dakar in Senegal or Accra in the Gold Coast (today Ghana), then flew across Africa using the well-established Takoradi Air Route (described in the previous Weekend Wings) to Khartoum in the Sudan. From there they flew to Aden in Yemen, then along the coast of the Arabian Peninsula and across the Arabian Sea to Karachi (then in India, now part of Pakistan). From there they flew South-East to Delhi and Calcutta, then North-East to the Arunachal Pradesh province of India, the base for the China airlift. (Click the map for a larger view.) The area of the airlift’s operations is within the black circle from North-East India to South-West China.

The China airlift was complicated by many factors. First was simply getting the goods there to be airlifted! They came by sea to India around the southern tip of Africa and, after the conclusion of the African campaign in 1943, through the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal. German submarines sank many of the ships. Those that survived sailed to ports on India’s West Coast and to Calcutta. From the ports their cargoes were placed in rail cars and made their slow, lumbering way to the airlift bases, where they were re-packaged for air transport.

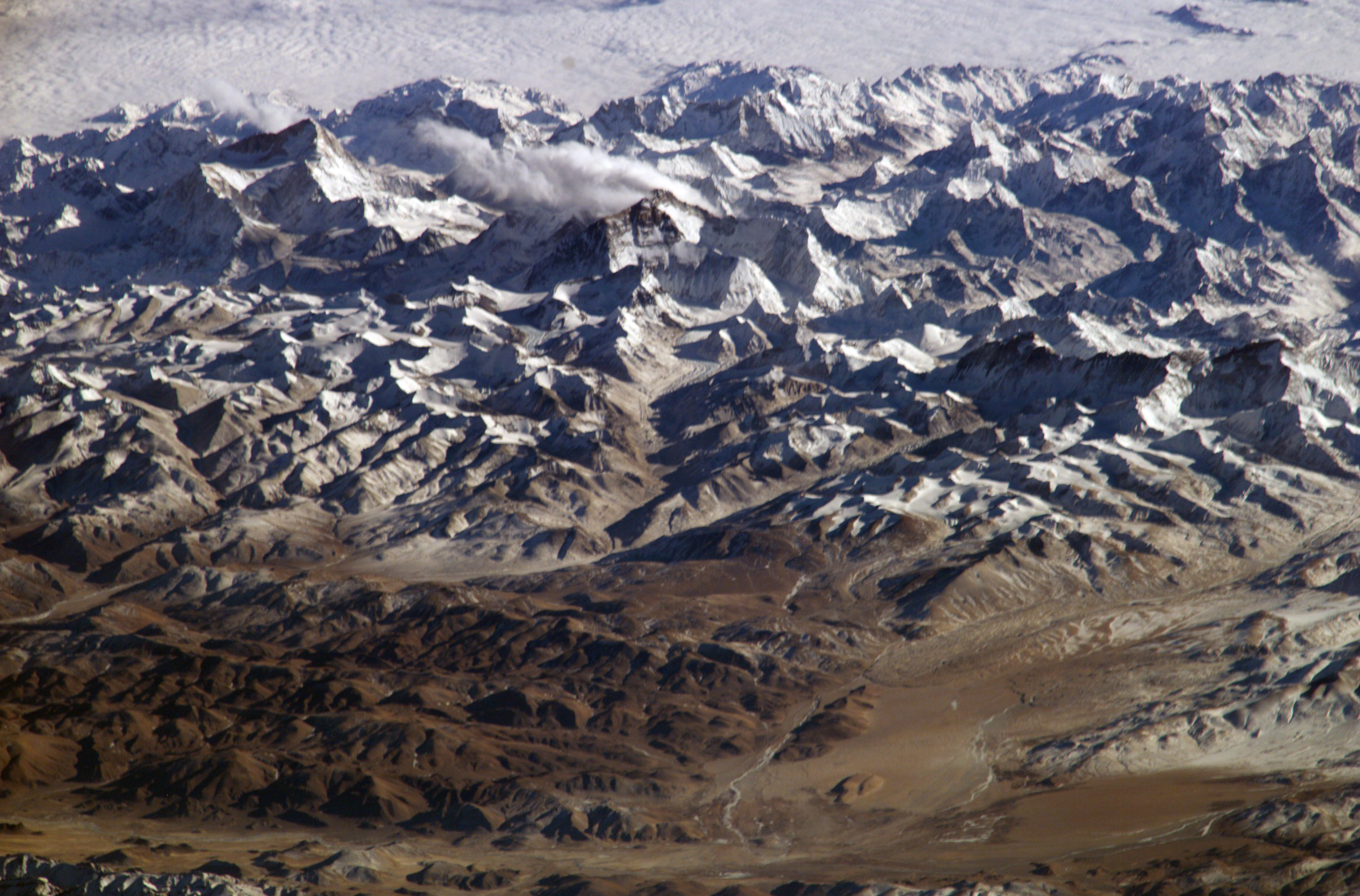

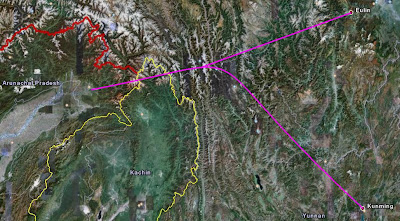

The second major problem was that the Japanese had occupied most of Burma. Their fighter aircraft could (and did) intercept any transports trying to fly directly across Burma to China, the most logical and feasible route. This meant that the aircraft had to fly a curved course, heading North-East into the Himalaya mountain range to avoid interception then turning South-East to Kunming or continuing East and North-East to other Chinese cities. The Himalayas were a huge obstacle to the aircraft of the day, which couldn’t climb high enough to cross over them (particularly when heavily loaded). They had to fly through valleys and past tall mountain peaks – and when the weather was poor and they couldn’t see very well, this was an enormously hazardous undertaking. The satellite image below gives you some idea of the terrain.

Viewed from the side, the air route through the Himalayas resembled a camel’s hump. That’s how the airlift got its famous (or infamous) name – The Hump.

The map and satellite image below show the problems clearly. The map illustrates how much of Burma was Japanese-occupied (the red-shaded portion), and how this forced the airlift to fly around the interception range of their fighters. The satellite image shows the incredibly rugged terrain, with the airlift course overlaid to show how the mountains formed a major obstacle.

Added to the problem was the immense difficulty of getting aviation gasoline, spare parts and vital equipment to the airlift bases (and from there to China to service and refuel the aircraft for the return trip to India). The Hump was at the end of a supply line over ten thousand miles long, competing for supplies with every other major US effort in the war – the Atlantic, Africa, Europe, England, the Pacific war, and so on. Initially the supplies for The Hump were a mere trickle compared to what was needed. Even when they arrived in India they had to compete for rail space with the goods to be transported by the aircraft. Small wonder that there was a perennial problem with maintenance and aircrew morale. It would be near the end of the war in 1944/45 before these problems would be solved.

The weather can only be described as ghastly. In India, the monsoon season brought torrential rains (usually over 200 inches in four months) that turned airfields into quagmires. Attempts to reinforce the runways with so-called Marsden Matting or pierced steel plating (PSP) were not very successful: the aircraft were so heavily laden that they simply drove the PSP deep into the mud, where it vanished without trace. Eventually tarmac and concrete runways were constructed, but this was only towards the end of the airlift – there simply wasn’t enough space to bring up the building materials on the already overcrowded railway network, and not enough labor to do the construction work.

Outside the monsoon season the dry, unbearably hot Indian summer took its toll. Dust got into the aircraft engines despite their filters and ruined them. One of the first commanders of The Hump, Colonel Edward Alexander, reported:

“Except on rainy days, maintenance work cannot be accomplished because shade temperatures of from 100 degrees to 130 degrees Fahrenheit render all metal exposed to the sun so hot that it cannot be touched by the human hand without causing second-degree burns”.

Insects, wild animals, mosquitoes bearing malaria, the threat of disease from polluted water sources, and the sheer drudgery of incessant labor against enormous odds made morale a constant problem.

On the air route to China the challenges were immense. The need to fly through the Himalayas was bad enough, but bad weather, low clouds, fog, very strong winds and violent turbulence added to the problems and caused many casualties. If pilots made it through one day, they knew they had to do it all over again on the way back – and then again, and again, and again. If they ran into mechanical difficulties there was nowhere to make an emergency landing, due to the mountainous terrain. The crews had to bale out and pray – they would be hundreds of miles from help and it was impossible to reach them in the mountains. If a crew strayed too far South, Japanese fighters were waiting to shoot them down.

What about the aircraft? Three types of plane initially flew The Hump. The first was the well-known C-47 Skytrain, the military version of the DC-3 Dakota airliner. This was a very reliable and serviceable aircraft, but had a limited cargo capacity and could not fly very high when fully loaded – a potentially lethal handicap in the Himalayas. Nevertheless, the aircraft gave good service.

The second was the Curtiss C-46 Commando. This was twin-engined, like the C-47, but much larger. It could lift up to 12,000 pounds of cargo and its engines (2,000 horsepower each as opposed to the 1,200 horsepower of the C-47’s engines) were powerful enough to get it to usable altitudes through the mountains. However, the engines were less reliable, causing many problems when spare parts ran short, and the aircraft had other vulnerabilities such as a tendency for gasoline to leak out of the fuel lines and pool in the fuselage at the wing root. This could be easily ignited by enemy fire or a stray spark, and was one reason why the C-46 was never a successful combat aircraft in Europe. Also, the more powerful engines consumed aviation gasoline very quickly. Very often when flying in heavy weather or against strong headwinds fuel would run low, causing many accidents.

The third transport was the Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express and its cousin, the C-109, which was a fuel transport with large gasoline tanks in the fuselage. These were modified versions of the B-24 Liberator bomber, with four powerful engines. They could carry a useful load, but had many problems. Chief among these was their sensitivity to center of gravity. A bomber such as the B-24 has its bomb bay in a fixed position, making it easy to design the aircraft around that center of gravity. A transport aircraft can have cargo loaded anywhere in the fuselage, making it vitally important to balance the load so that the aircraft is stable. Since the C-87 shared the B-24’s center of gravity design, it meant that any instability in the load would make the aircraft very difficult to handle.

The C-87 was also particularly susceptible to icing in bad weather (a defect shared with the B-24 bomber). In the Himalayas, where icing was a common problem, this caused many accidents. Furthermore, the fuel lines crossed inside the crew and cargo compartment – and often leaked. This threatened to gas the flight crew with the fumes from the fuel and posed a major fire hazard. Finally, although almost 300 C-87’s were built as new aircraft, many others were converted in the field from B-24 bombers. Those selected for conversion were mostly older aircraft that had seen hard use – after all, bomber commanders wanted to keep their newer aircraft for themselves. This meant that the converted bombers were often slow, underpowered and had poor serviceability due to being worn out.

These three types of aircraft provided most of the airlift on The Hump until 1944. It was only then that the new C-54 Skymaster became available. This purpose-built freight aircraft was superb, and could handle conditions on The Hump with ease. By 1945 it had taken over most of the flying – just in time for the end of the war.

The initial airlift effort was miserably inadequate, flying only a few hundred tons every month. By the end of 1943 the effort had expanded to the point where up to 10,000 tons per month was being transported, but at an incredible cost in lives and lost aircraft. Clearly something had to be done.

The US Army Air Force sent in General William H. Tunner to take charge of the airlift. During 1944 he succeeded in revolutionizing the operation. He stabilized personnel turnover, introduced regular maintenance schedules (which proved so effective that the US Air Force uses them to this day), and brought in the C-54. He insisted on fighter escorts for his transport flights, thus enabling them to fly further to the South and avoid the worst of the Himalayas, and also publicized the enormous efforts being put into The Hump, gaining for pilots and crews the admiration and respect of the rest of the world. This greatly improved morale – previously the Hump personnel had deemed themselves forgotten and ignored.

Despite all obstacles, and particularly under the leadership of General Tunner, The Hump turned out to be a success. It’s estimated that from May 1942 to September 1945 some 650,000 tons of cargo and 33,400 personnel were transported in both directions, requiring about 1.5 million flight hours. These figures would not be exceeded until the Berlin Airlift of 1948. General Tunner would lead that operation too, and the principles he established on The Hump to handle massive airlift operations are in use to this day.

However, this success came at a heavy price. A total of 468 US crews and 46 Chinese crews died flying The Hump – more than 1,500 personnel. During some months more than 50% of the planes that departed never made it back. The casualty rate was at times as bad or worse than that of the bomber crews of the US Eighth Air Force assaulting Germany – but without the publicity and medals that the bomber crews received.

So, next time you take an airline flight or see a military transport aircraft flying overhead, remember those who flew The Hump. They paved the way (all too often with their lives) for the convenient, flexible, global air transport networks of today.

Peter

Phew!

What would us humans not do to kill each other!

One old man in my village recounted how one morning during the war they woke up to see the shining wreck of a plane in a distant hill. Soon white men descended, employed many villagers to make a makeshift tarmac, flew in an aircraft , collected the remains and flew out again. This was in the hilly area of India in hump route.

Many others apparently got left behind.

Thanks for the memory of the Flying Tigers. Brave men! They were indeed dependent on cargo planes from India, since after May 1942 there was no overland route until one was built through northern Burma. After the original volunteers were disbanded in July 1942, the 23rd Fighter Group was commanded by a former C-47 pilot, Col. Robert Scott. More about all this in Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and His American Volunteers, 1941-1942 or at the Annals of the Flying Tigers. Blue skies! — Dan Ford

I will be going to AP state in April 2008 working on a flood project for the Asian Development Bank. I will be working in some of the areas where planes were lost. I will ask questions on missing planes in remote villages I will visit.

A neighbor up the street from me flew the Hump. He wore the (iirc) 14th airforce cap whenever I saw him on the street. He spoke once of attending a banquet with other pilots given by some local government officials in China. At one point his buddy turned to him and referring to the Chinese man on his side, said to Mickey, "This man thinks he's going to take over China." That was Chou En Lai, Mao's ambassador to the Nationalist Chinese forces.