Instead of any particular aircraft, this week I thought I’d bring you a few stories from the lighter side of aviation. The first part contains stories that are true, arranged in chronological order. I’ve tried to select accounts that won’t be familiar to most readers, so as to give you something new to enjoy. The second part contains a few of my favorite aviation jokes and comic sayings.

These, of course, are only a few of many possible entries. I’ll save the others for future posts in this series.

THE TRUE STORIES

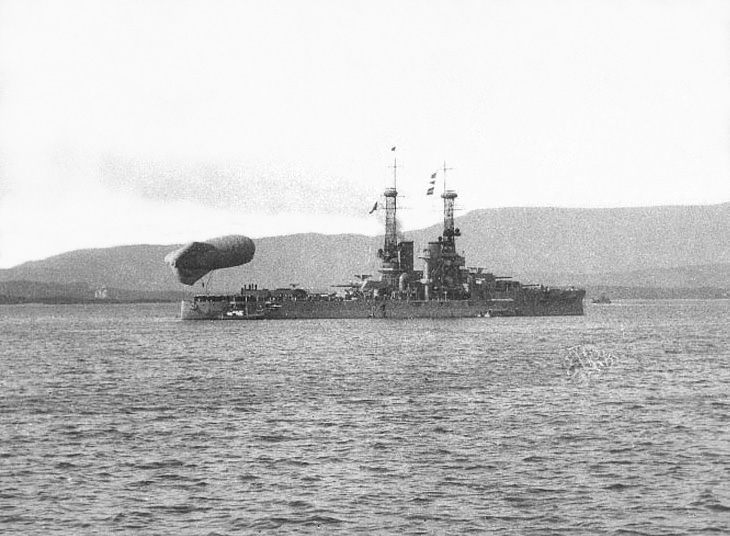

During the First World War US naval aviation was in its infancy. One innovation was that battleships frequently towed kite balloons, carrying observers in a basket beneath them. They could be towed at altitudes of up to a thousand feet or more. The idea was that from their greater height, they could see over the horizon and alert their ships to the presence of an enemy. USS Utah is shown below with her kite balloon moored at the stern.

This sometimes led to unforeseen problems, particularly when flying the balloons while the ships were in line-astern formation, as illustrated in 1917 by a signal from USS Texas to USS New York:

PLEASE ASK YOUR BALLOON OBSERVER TO STOP PISSING ON MY NAVIGATOR.

In 1940 the ship recognition displayed by Royal Air Force pilots was sometimes lamentably inaccurate. This was rather forcibly borne out by a signal from a British submarine during the Norwegian campaign:

RETURNING TO BASE. EXPECT TO ARRIVE 18H00 IF FRIENDLY AIRCRAFT WILL STOP BOMBING ME.

Other RAF pilots had similar problems identifying friendly forces on land. The famous novelist, John Masters, had a stellar Army career during World War II. In the second volume of his autobiography, “The Road Past Mandalay”, he recalls one incident in the Middle East with the RAF.

Two twin-engined planes appeared from the west and came in with single front guns firing. This was nothing, and the return fire of twenty Bren guns lashed up at them. They roared low overhead, bullets ripping into their bellies, and dropped about twenty small bombs in our B Company area, damaging no one. They swung round and came in again. More bombs, more machine-gun fire from the nose. As one of them wheeled, a few hundred yards out over the desert, I distinctly saw the RAF roundels on its side. It leaped to my mind, and to Willy’s at the same time, that from their shape they could only be Blenheims, a British light bomber.

“Cease fire!” the Colonel yelled.

The nearest man to me was a machine-gunner who had got a Vickers gun loosened on its tripod so that it would make an effective anti-aircraft weapon. The Blenheim came in, our machine-gunner took a good lead and pressed the buttons, while the aircraft’s fire ripped somewhere over our heads.

“Cease fire!” I bellowed at the machine-gunner. “Ours, ours!”

“Why’s he firing at us, then?” the gunner asked politely, swinging round and sending a hundred rounds up the Blenheim’s arse.

A little later two battered Blenheims landed at Mosul and reported a successful raid on the French at Tel Abiad, some sixty miles to the north of Raqqa. By then the radio waves were boiling with furious signals from Willy. Next day we heard that the officer responsible for the error had been removed from command of his flight. Willy looked sick with worry. He didn’t want the chap to suffer for an honest mistake. Dashed brave attack they’d put in, really.

I made two mental notes to add to the many I was accumulating through the campaign: (One) A loaded warplane is like a pregnant woman. When its time comes, it is under a compulsion to drop its burden, however unsuitable the circumstances. (Two) Airmen, though splendid at finding their way to Gosnau-Feldkirchen in night, fog and rain, cannot tell Raqqa from New York in broad daylight. Some soldiers were inclined to believe that no airman’s brain functions at all under 3,000 feet, but I thought this was an over-simplification.

In 1943/44 Wing Commander W. G. G. Duncan Smith of the Royal Air Force was leading a wing of Spitfires in the Italian campaign. In his book “Spitfire Into Battle” he describes the joy of overhearing radio conversations from the famous “Tuskegee Airmen“, the 332nd Fighter Group of the US Army Air Forces. At the time they were flying P-47 Thunderbolts.

One conversation he recalls went something like this:

“Red Leader to Green Leader, enemy transport on the road at two o’clock below. Go down and strafe ’em, over.”

Silence.

“Red Leader to Green Leader, go down and attack that enemy convoy, over.”

Silence.

“Red Leader to Green Leader, did you hear me?”

“Green Leader to Red Leader. Man, look at all dat flak! You’s got the Distinguished Flyin’ Cross. Why don’t you go down, an’ show us some distinguished flyin’?”

Another he reported went along these lines:

“Red Leader to Red Two, if dat’s you behind me, waggle your wings, over.”

Silence.

“Red Leader to Red Two, I say again, if dat’s you behind me, waggle your wings, ’cause you sure looks like a Focke-Wulf. Over.”

Silence.

“Uh-oh. You’s a Focke-Wulf!”

(Seen from directly in front, the German Focke-Wulf Fw-190A, shown below, and the US P-47 Thunderbolt, shown above, were sometimes hard to distinguish, particularly in the stress of combat.)

In 1943 arrangements were made for the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy to obtain F4U Corsair fighters from the USA.

The early models of this aircraft had proved so difficult to land on carriers that the US Navy had banished them to land bases: but the Fleet Air Arm was so desperate for modern fighters that “beggars couldn’t be choosers”. Several squadrons were shipped over to the USA to learn to fly and fight their new aircraft. The Senior Pilot (and later Commanding Officer) of 1833 Squadron was Norman Hanson, who published an excellent memoir of his World War II service, “Carrier Pilot”. The following are extracts from his book.

Corsairs filled the hangar floor and I must say that, of all the aircraft I had seen, they were the most wicked-looking bastards. They looked truly vicious and it took little imagination to realize why so many American boys had found it difficult, if not well-nigh impossible, to master them, especially in deck-landing. We stared at them and hadn’t a word to say … I tried one of the typewriters, a beautiful machine. I found a sheet of quarto and typed; and what I typed was my last will and testament. I saw no reason why a Corsair shouldn’t kill me when it could obviously kill so many other lads without any trouble. It certainly wasn’t going to catch me unawares.

. . .

We blazed away thousands of rounds of ammunition at towed targets, taking it in turn to tow the drogue and hoping that the boys would remember that we were pulling, not pushing, the confounded thing.

Early one morning young Monteith … pressed his trigger to produce the Shot Of The Year. He was doing a high-side run on the drogue – diving on it from one side, from a height advantage of 500 or 600 feet – and failed to notice that far, far below him was one of the pretty little islands that adorn the coast of Maine, tastefully inhabited.

Two of his .5-inch bullets, fair-sized chunks of armor-piercing steel, travelling at the speed of sound, tore through the outer wall of a hotel into a bathroom, where a retired Colonel was leisurely bathing his middle-aged frame. Having noisily effected their entrance, the bullets then proceeded to hammer their way through the side of his bath at a downward angle of some 60 degrees, zipped across his thighs into the water and perforated the bath on the other side, thereby making completely unnecessary the removal of the plug for emptying purposes.

Needless to say, such marksmanship didn’t go down well.

. . .

We landed on the Navy airfield [at Norfolk, Virginia] and our Corsairs were to be hoisted by crane aboard the ship [HMS Trumpeter, an escort carrier] as deck cargo.

To reach the docks, we had to taxi our planes through the outskirts of the town, with our wings folded, causing quite a furore amongst the street traffic! It was something our training had never envisaged when we held out our right hand to signify we intended to make a right turn, to be answered by the traffic cop with the customary wave of his hands and a big grin on his face!

. . .

Monteith was responsible for producing the only incident on the airfield [at Ringway, UK]. During a touch-down for Johnny Hastings [the Landing Signal Officer] one afternoon in a bit of a crosswind, he clipped a wingtip on the concrete runway at the moment of opening up again to do another circuit. His lack of experience – and probably a bit of panic – now proved his undoing. Instead of cutting his throttle and making the best of a bad job, in which event he would have got away with a shaking-up and a new wingtip, he pressed on. The great Corsair, under full throttle, careered across the grass bouncing on the end of the port wing, which took a very poor view of such treatment.

It so happened that the NAAFI van had just rolled up to the squadron with tea and scones. The CO and I were standing at the office window, cups in hand, when we were astonished to see a Corsair fly past – literally! – the window, busily engaged in completing a slow roll. As we looked at one another, unbelieving, there came the most monumental crash from our left. Monty had hit an earth revetment near the office which had canted his aircraft on to one side, breaking off a wing at the root. When we erupted from the office and ran across the field to a sizeable gap in the hedge, we saw the machine reclining on its belly, smoking gently amid the turnips. No wings, no prop, no undercarriage. Monty was clambering out. He looked somewhat vague. The destruction among the turnips was stupendous.

“What happened?” he asked, stumbling away with his parachute waggling behind him like a monstrous bustle. He was still saying it an hour later, sitting in an office chair to which we had led him. He hadn’t a scratch.

In 1944 Fleet Air Arm aircraft, flying from Royal Navy carriers of the Eastern Fleet, raided oil refineries and the Japanese base at Sabang in the Dutch East Indies. Afterwards the Commander made this signal to report success:

WE CAUGHT THE NIPS WITH THEIR HEADS DOWN AND THEIR KIMONOS UP.

In 1944, the 1st Combat Cargo Squadron was sent to India from the USA, using the C-47 Skytrain:

and, later, the C-46 Commando:

to support operations in the China-Burma-India theater. Their primitive living conditions in India left something to be desired. An account of the squadron recalls:

The normal method of insect control around latrines was to add fuel oil, to keep insect larvae from hatching. In the heat of the day, fumes would naturally rise. Some GI’s would ‘light up’ while sitting on the can, and the resultant explosions usually lifted the roof, cleaned out the pit and abruptly removed the occupants. Another danger was snakes. One airman was sitting in the latrine one night when a python slithered across his lap. He reported being ‘somewhat startled’. On another occasion, two local laborers were repairing a walkway to a latrine when one lifted a flat rock to find two cobras underneath. The snakes weren’t happy at being disturbed, and reared up, hissing loudly, hoods extended. Witnesses reported that the laborers were still running at full speed when they passed out of sight into the jungle on the far side of the airfield.

In early 1945 the unit was transferred to China, joining the US 14th Air Force, led by Major-General Claire Chennault. One of their duties was moving Chinese troops to different parts of the country, accompanied by their pack animals. The mules caused some interesting problems. The same account reports:

On one trip, the forward crossbar had worked loose, and one of the mules pushed his head into the cockpit. With the bar still there, he couldn’t get all the way in, but he expressed his displeasure by snapping and snarling at the radio operator, who squeezed in beside the co-pilot, trying to make himself as small as possible. A quick trip to a higher altitude, inducing temporary oxygen starvation, was enough to render the mule passive and restore order to the flight.

Those mules caused us a real maintenance headache. Scared animals urinated in the planes, and the straw we laid down on the decks didn’t absorb it all. This caused tail control surface cables running beneath the floor to corrode and require premature replacement. We found out about the problem when the cables on one plane snapped clean in two while taxiing out for take-off. After investigating, it became standard operating procedure to double-check the cables on all aircraft used for animal transport three times more often than usual, just in case. No-one wanted to find out about corroded cables at five thousand feet!

In 1945 the Royal Navy was operating four aircraft carriers in the Pacific in support of the US Fleet, operating in the Okinawa area. One of the carriers was struck by a Japanese kamikaze (suicide) aircraft, fortunately sustaining only light damage. She exchanged signals with Vice-Admiral Philip Vian, commanding officer of the carrier division.

Carrier to Vice-Admiral Vian: LITTLE YELLOW BASTARD.

Vice-Admiral Vian to carrier: ARE YOU REFERRING TO ME.

Upon the surrender of Japan in 1945, the US Third Fleet was operating off its coast. Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey was aware that fanatical Japanese might disobey their Emperor and still launch kamikaze attacks against his ships. He therefore sent the following signal to his carriers:

INVESTIGATE AND SHOOT DOWN ALL SNOOPERS – NOT VINDICTIVELY, BUT IN A FRIENDLY SORT OF WAY.

In 1966 a C-124 Globemaster II cargo aircraft was taxiing at Rhein-Main AFB in Germany, when it came face-to-face with an F-4 Phantom II fighter-bomber coming the other way. Both aircraft halted.

The F-4 pilot radioed, “I have right of way. What are you going to do?”

The C-124 pilot opened his clamshell load doors (shown below), started forward and replied, “I’m going to eat you!”

A Piper Seneca twin-engined light aircraft, similar to the one shown below, crashed in Florida on December 23rd, 1991. This is the official report of the National Transportation Safety Board on the accident. Read between the lines and all becomes clear . . .

Aircraft: PIPER PA-34-200T, registration: N47506

Injuries: 2 Fatal.THE PRIVATE PILOT AND A PILOT RATED PASSENGER WERE GOING TO PRACTICE SIMULATED INSTRUMENT FLIGHT. WITNESSES OBSERVED THE AIRPLANE’S RIGHT WING FAIL IN A DIVE AND CRASH. EXAMINATION OF THE WRECKAGE AND BODIES REVEALED THAT BOTH OCCUPANTS WERE PARTIALLY CLOTHED AND THE FRONT RIGHT SEAT WAS IN THE FULL AFT RECLINING POSITION. NEITHER BODY SHOWED EVIDENCE OF SEATBELTS OR SHOULDER HARNESSES BEING WORN. EXAMINATION OF THE INDIVIDUALS’ CLOTHING REVEALED NO EVIDENCE OF RIPPING OR DISTRESS TO THE ZIPPERS AND BELTS.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident as follows:

THE PILOT IN COMMAND’S IMPROPER INFLIGHT DECISION TO DIVERT HER ATTENTION TO OTHER ACTIVITIES NOT RELATED TO THE CONDUCT OF THE FLIGHT. CONTRIBUTING TO THE ACCIDENT WAS THE EXCEEDING OF THE DESIGN LIMITS OF THE AIRPLANE LEADING TO A WING FAILURE.

All I can say is – what a way to go!

And finally, just to show that “flying” doesn’t necessarily refer only to aviation, the following theatrical reminiscence is provided by Richard Finkelstein.

Around 1981 we were doing a BIG production of Rogers & Hammerstein‘s “Cinderella“. We were using all the tricks and then some. We had 9 people “flying”, the coach, the magic transformations….you name it.

The show calls for two “instant” costume changes, and we were doing these the way they were originally done on Broadway. For the first big change, the “feather woman” had to change to the fairy godmother….after first flying in. For this we used a souped up old technique. She was overdressed in a costume made in one piece. The back had a big handle on a cord incorporated into the design. At the appropriate time the actress was to meander over to our large fireplace. A team hiding inside the unit was to grab the handle and on cue, with a flashpot covering, literally take off running at full speed, ripping the outer layer from her body at the speed of a whip crack.

Now, to set up the imagery, our fairy godmother was a dainty soul. Plus she was really weighted down. First the two massive costumes, then the somersault harness, then, as I recall, THREE battery packs. One for the wand, one for the wireless mike….and who knows what the third was for.

Well, the first time to try it all out was the first time the orchestra was in rehearsal with the cast. These were in the days when the arts could hire larger orchestras. But with union considerations, the push was to keep things moving as efficiently as possible.

The cue line: “Don’t you know … I’m your fairy godmother!” is where the magic is supposed to happen. The moment came, the crew took off at the requisite gallop and – POOF! – up the chimney the fairy godmother got sucked!

It was so funny that it took about 30-40 minutes before anyone could attempt the scene again without laughing. The worst were the orchestra members. It made their millennium.

The moral: Who says velcro won’t hold?

THE NOT-NECESSARILY-TRUE SECTION

As the Concorde was being prepared for its first flight, two British workmen were reportedly assigned to the job of painting the aircraft. A special paint had been developed to cope with the stresses of high-speed flight.

One of the men said to the other. “This paint smells like gin.”

The other guy said, “I thought so too. Shall we try it?”

They both had a swig. One thing led to another, and by the end of the shift, they’d drunk 22 cans between them. Drunk as skunks, they returned to their homes, and went straight to bed.

The next morning, one of the men woke up with an enormous hangover. Getting out of bed, he fell flat on his face. As he got up, he noticed little wheels growing out of the soles of his feet.

“What on Earth . . . ???” he exclaimed.

He made his way to the bathroom and looked in the mirror. He couldn’t believe what he saw. He now had a 7 inch long pointed nose, his shoulders were pushed back, and his arms had flattened.

“What the hell’s going on?” he muttered to himself.

Just then the phone rang. It was his colleague from the day before.

“Thank God you’ve phoned” he said. “I’ve got wheels growing out of my feet, a long pointed nose and flat arms. What’s happening?”

His mate said, “I woke up the same way. Whatever you do, don’t fart. I’m phoning from Bahrain!”

ALLEGED GERMAN TRANSLATIONS OF AVIATION TERMS

AIRCRAFT – Ein Wingenwaggenmaschinen.

ENGINE – Ein Ubergrosser Biggenmother Noisenmaker.

PROPELLER – Ein Airfloggenfan Pushenthruster.

JET – Ein Skullschplittenscreemen Firespittensmoken Airpushenbackenthrustermaker.

CONTROL COLUMN – Das Pushenpullen Bankenyankenschtick.

RUDDER PEDALS – Das Tailschwingen Yawmakenmaschinen.

PILOT – Ein Pushenpullen Bankenyankenschtick und Tailschwingen Yawmakenmaschinenoperator.

PASSENGER – Ein Strappeninderbackendumbkopf.

LUGGAGE – Bitzundpeeces Someplaceelsearriven.

AIRLINE PILOT – Ein Grossenoverpaidundunterwerken Whinencomplainer Biggenschmuck.

PARACHUTE – Ein Stringenthingen Floatencotton Asspreservenmaschinen.

FAA INSPECTOR – Ein Friggenschmuck Uberbureaucratische Dumbkopfwiener.

HELICOPTER – Ein Flingenwingenfloppenbladenmaschinen.

RULES OF FLYING

- Every takeoff is optional. Every landing is mandatory.

- If you push the stick forward, the houses get bigger. If you pull the stick back, they get smaller. That is, unless you keep pulling the stick all the way back, then they get bigger again.

- Flying isn’t dangerous. Crashing is what’s dangerous.

- It’s always better to be down here wishing you were up there than up there wishing you were down here.

- The only time you have too much fuel is when you’re on fire.

- The propeller is just a big fan in front of the plane used to keep the pilot cool. When it stops, you can actually watch the pilot start sweating.

- When in doubt, hold on to your altitude. No one has ever collided with the sky.

- A ‘good’ landing is one from which you can walk away. A ‘great’ landing is one after which they can use the plane again.

- Learn from the mistakes of others. You won’t live long enough to make all of them yourself.

- You know you’ve landed with the wheels up if it takes full power to taxi to the ramp.

- The probability of survival is inversely proportional to the angle of arrival. Large angle of arrival, small probability of survival and vice versa.

- Never let an aircraft take you somewhere your brain didn’t get to five minutes earlier.

- STAY OUT OF CLOUDS!!!!! The silver lining everyone keeps talking about might be another airplane going in the opposite direction. Reliable sources also report that mountains have been known to hide out in clouds.

- Always try to keep the number of landings you make equal to the number of take offs you’ve made.

- There are three simple rules for making a smooth landing. Unfortunately no one knows what they are.

- You start with a bag full of luck and an empty bag of experience. The trick is to fill the bag of experience before you empty the bag of luck.

- Helicopters can’t fly; they’re just so ugly the earth repels them.

- If all you can see out the window is ground that’s going round and round and all you can hear is commotion coming from the passenger compartment, things are not at all as they should be.

- In the ongoing battle between objects made of aluminum going hundreds of miles per hour and the ground going zero miles per hour, the ground has yet to lose.

- Good judgment comes from experience. Unfortunately, the experience usually comes from bad judgment.

- It’s always a good idea to keep the pointy end going forward as much as possible.

- Keep looking around. There is always something you have missed. Isn’t that why they created checklists!

- Remember, gravity is not just a good idea. It is the law and it is not subject to repeal.

- The three most useless things to a pilot are the altitude above you, the runway behind you and a tenth of a second ago.

- There are old pilots. There are bold pilots. However, there are no old, bold pilots.

I hope you enjoyed the stories. More in a future Weekend Wings.

Peter

Great post.

“Good judgment comes from experience. Unfortunately, the experience usually comes from bad judgment.” – story of my life…

Story of your Law.

I really enjoy your WW series – I wish I had the time to do the research. But I’ll DAY-UM sure read the fruits of your labor. Thankee.

We need to see footage of the ’66 C-124/F-4 incident.