I’ve been fascinated to discover the advances in high-resolution imaging sonar that have come along over the past few years.

My interest was sparked by the recent discoveries of the wrecks of HMS Hunter in a Norwegian fjord, and HMAS Sydney off Australia. Both were located by sonar, and have been photographed.

Having blogged about both, I began investigating the ‘state of the art’ in sonar location of shipwrecks. I found that an outfit called Adus, in the UK, has developed some astonishing technology that produces sonar pictures as clear, if not clearer than, underwater photographs. This is particularly important for deep-lying wrecks, or those where there’s not much light, as a camera’s field of vision is strictly limited. On the other hand, a high-resolution imaging sonar can capture a picture of an entire wreck without difficulty.

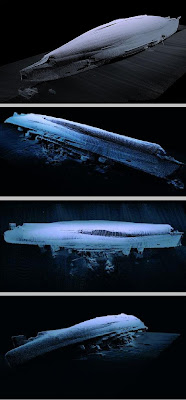

I’ve put together a selection of pictures to illustrate the point. First is the battleship HMS Royal Oak, sunk by a U-boat in Scapa Flow in 1939. In life, she looked like this (click this and other pictures to enlarge):

Her wreck now lies on the seabed of Scapa Flow, and is a designated war grave. The four photographs (or, rather, sonar scans) below show her clearly.

You can clearly see where the first torpedo blew off the underpart of her bow, and on her starboard side can be seen the hole torn by the remaining three torpedo hits.

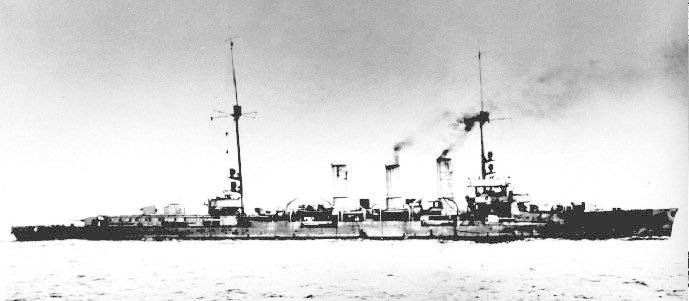

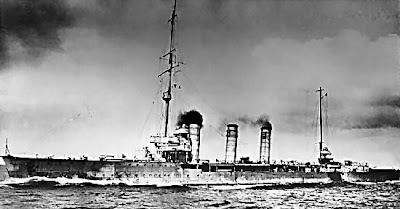

Also in Scapa Flow are the wrecks of several German warships from World War I, which were scuttled there in 1919. Here’s SMS Dresden, a light cruiser, as she was in life:

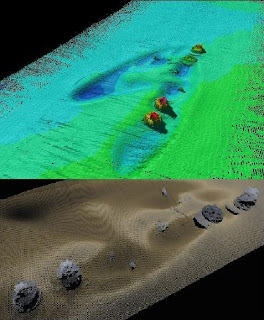

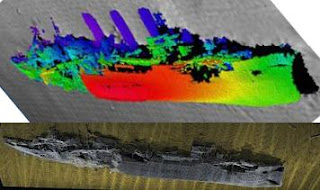

And this is how she looks on the bottom. The white oval highlights where her armored deck has begun to peel away from the hull near the bow. The damage near her stern is the result of salvage efforts to recover her engines and other heavy metal items. She’ll disintegrate in due course, as all wrecks do, but she’s still remarkably well preserved.

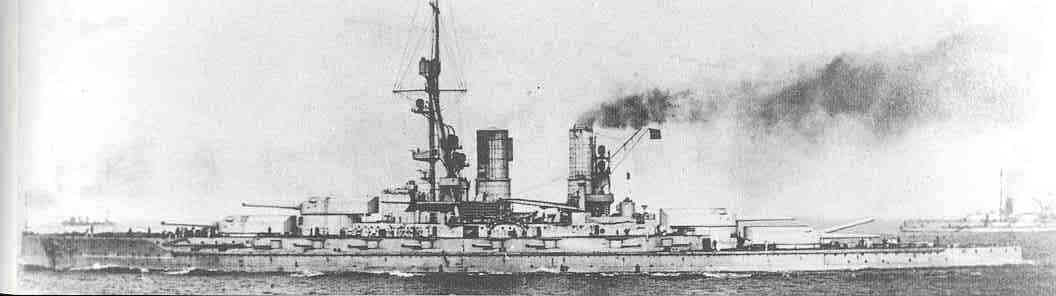

Next is the battleship SMS Bayern. Here she is in life:

And what little remains in death. Her hull rested upside-down on the sea-bed. When it was salvaged, in 1933, her main gun turrets fell out as it was raised, and they now rest on the sea-bed. The second depression in the sea-bed, above the turrets, is where the Bayern‘s hull was dropped during the salvage! It hit the sea-bed hard enough to make the big dent that’s still visible. I’m amazed that sonar can show it so clearly.

Finally, here’s SMS Brummer, a minelaying cruiser, as she was in life:

And as she now lies on the bottom of Scapa Flow:

Note that in the first density scan, her funnels and superstructure are visible as ‘shadows’ on the sand. They’re actually either buried beneath the sand, or rotted away, leaving only traces of iron oxide where they once were. They’re not visible in the second, high-res scan for that reason: but the first scan shows their former presence. Fascinating stuff!

You can see more pictures of the sunken warships in Scapa Flow in an article on the Divernet Web site. There’s a good article about this technology here. Adus has also launched another Web site, Wrecksight, which will host more such pictures in future.

Peter

Thank-You for the history lesson. Keep the lessons coming.Rick