Last week I published the first of a three-part Weekend Wings series about the Supermarine Spitfire, possibly the most significant fighter aircraft of all time in terms of its performance, versatility and operational record. That article examined the development and early versions of the Spitfire and its operational career up to and during the Battle of Britain.

In this second part of the series I’ll examine the Spitfire’s operations during the remainder of World War II, with reference to its ongoing development and new versions that substantially improved its performance. I won’t go into too much technical detail about the various Marks of the aircraft, as there’s so much information involved that this article would become no more than series of engineering reference notes. Those who’d like to learn more about the different Marks may consult the following references:

between Spitfire Marks

Another article detailing Spitfire variants

Spitfire versions compared

to their primary German opponents

If you’d like to know more about the development of the engines that powered the Spitfire, consult these links:

At the end of the Battle of Britain the Spitfire had captured the imagination of the British public as the savior of the nation, despite the fact that Hurricanes far outnumbered Spitfires in Royal Air Force (RAF) service and had shot down many more German aircraft. The higher-performance Spitfire had also earned the high respect of the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, to such an extent that the German fighter leader Adolf Galland had famously demanded of Hermann Goering that his squadrons be equipped with Spitfires! (This did little to enhance Galland’s short-term career prospects.)

Luftwaffe bombing raids on Britain continued, but were conducted almost exclusively under cover of darkness. Efforts were made to use the Spitfire, Hurricane and other single-engined aircraft as night fighters, but with the technology of the day and lacking (as yet) an effective airborne radar installation, these were unsuccessful. Twin-engined aircraft such as the Blenheim, the Beaufighter and later the Mosquito proved far more successful in this role.

RAF Fighter Command began almost immediately to engage in operations over occupied France. They were intended to develop an offensive-minded spirit and ensure that the Germans could not rest easy in their newly-gained territories: but the RAF was soon to find that these operations were costly in the extreme. All the disadvantages faced by the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain now applied to the RAF. They had to operate short-ranged fighter aircraft over unfriendly territory, where they had only a limited time to engage in combat before shortage of fuel forced them to withdraw. The Luftwaffe, on the other hand, could now operate near many friendly bases and use its radar equipment to predict RAF incursions and respond to them. The loss ratio immediately favored the Luftwaffe and would continue to do so for some time.

In addition the RAF had to improve the performance of its aircraft. The Spitfire Marks I and II had proved equal to the Messerschmitt Bf 109E model they’d encountered in the Battle of Britain, but the Hurricane had been clearly outmatched by the German aircraft: and by late 1940 the improved Messerschmitt Bf 109F model (shown below) began to appear in squadron service. It was considerably superior to its predecessor – and to the existing Marks of Spitfire. (As always, click the picture for a larger version.)

Clearly, the Spitfire’s performance would have to be improved to counter this new threat. Fortunately a solution was at hand. The Mark I/II airframe was fitted with the Merlin series 45 engine, producing 1,440 hp and giving a substantial increase in performance. In addition, a new type of Spitfire wing accommodating two 20mm. cannon and four .303-inch machine-guns had now had its teething troubles sorted out and went into large-scale production. The result was the Spitfire Mark V, the most-produced of any Spitfire model. It began to enter squadron service in early 1941 and proved a match for the Bf 109F.

The Mark V saw more widespread service than any other Mark of Spitfire. Many were sent to North Africa, fitted with an enlarged sand filter that reduced performance but allowed operation in desert conditions, as shown below (note the bulge of the filter beneath the nose).

More were flown to Malta to reinforce the aerial defenses of that island, including dozens that flew off British and US aircraft-carriers.

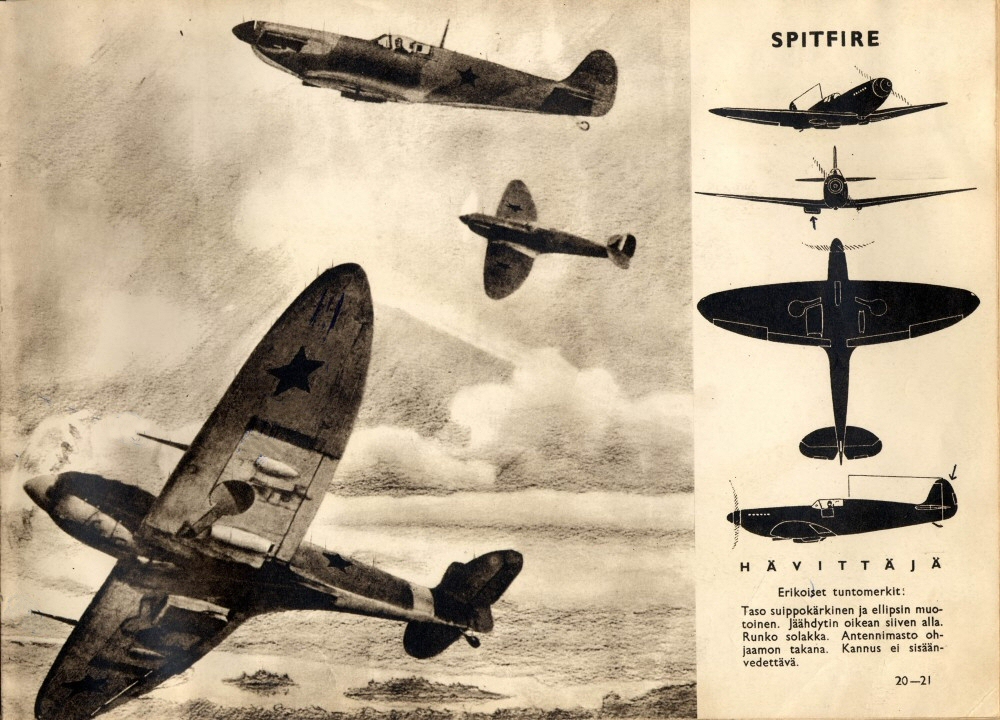

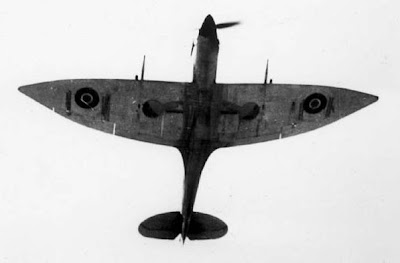

Mark V’s were also sent to the Soviet Union to aid in its fight against Germany after Operation Barbarossa commenced in June 1941. Britain would supply a total of over 1,300 Spitfires of several Marks to the Soviet Union over the course of the war, along with almost 3,000 Hurricanes. An interesting relic from the period is a 1942 Finnish Air Force aircraft recognition guide depicting fighters in service with the Soviet Union (remember that Finland fought alongside Germany against the Soviet Union). This is how they depicted the Spitfire Mark V in Russian markings:

The Luftwaffe‘s introduction in late 1941 of the Focke-Wulf FW 190 fighter, and soon thereafter the further improved Messerschmitt Bf 109G, spelled trouble for the Spitfire Mark V, which couldn’t match either of them. The Spitfire Mark IX was the answer. Fitted with a double-supercharged Merlin engine it was at least equal to either German aircraft. It would be the second-most-produced model of Spitfire and give satisfactory service until the end of the war. It entered service in 1942, making its combat debut over Dieppe during Operation Jubilee.

Both Mark V and Mark IX Spitfires would receive modifications to improve their performance in particular applications or missions. A common modification was to remove the elliptical wing-tips, leaving a so-called “clipped wing” that improved roll rate considerably. With more powerful engines such Spitfires offered greatly improved performance at lower altitudes, particularly in a fighter-bomber role. The two-part video below shows an airshow display by a surviving Spitfire Mark V with clipped wingtips, today part of the Shuttleworth Collection in England. It offers unique views taken from inside the cockpit during flight.

Other modifications included pressurized cabins and extended wingtips to improve performance at higher altitudes. The latter were incorporated in the Mark VI in England, along with more powerful engines, and also improvised in the field in Egypt (as mentioned in Weekend Wings #9). The difference in wingtip profile can be clearly seen in the photographs below, the top one being a standard Spitfire Mark V and the lower a Mark V with extended wingtips.

By now limitations in the Spitfire/Merlin airframe/engine combination were becoming apparent. The Air Ministry had planned to replace the Spitfire in 1943 with the Hawker Tornado, a new fighter using the Rolls-Royce Vulture engine. However, the latter experienced so many problems during development that it was cancelled. The Tornado would be further developed into the Typhoon, using the Napier Sabre engine: but a new and more powerful fighter was urgently needed to counter ongoing German developments.

Fortunately, as early as 1939 Supermarine’s chief designer, Joe Smith, had envisaged using the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine as a more powerful replacement for the Merlin engine in the Spitfire. After many delays caused by the urgent operational demand for Merlin-engined Spitfires, in November 1941 the first Griffon-powered prototype took to the air. The Griffon was only slightly larger than the Merlin in physical size but had 36% greater capacity (36.7 liter versus 27 liter) and produced far more power. It proved an instant success in the Spitfire, despite requiring aerodynamic modifications to allow the airframe to handle the additional power. The prototype Griff0n-engined Spitfire is shown below.

In a fly-off between a prototype Typhoon, a captured FW 190 and the prototype Griffon-engined Spitfire in July 1942, the latter beat both of the other aircraft convincingly. This caused a sensation at the Air Ministry, which had never imagined that such an improvement in the performance of the Spitfire was possible, and ensured the ongoing production of the Spitfire through many more variants. The most-produced Griffon-engined version would be the Mark XIV, which proved fast enough to intercept V-1 flying bombs and continued to serve in the air superiority mission until the end of the war. A later development, the Mark XVIII, coming right at the end of the war, featured a cut-down rear fuselage and bubble canopy similar to the P-51D model of the Mustang. A photograph and video of the Mark XVIII are shown below. Turn up the sound to hear the roar of the Griffon engine – and note the five-bladed propeller needed to make use of all that power!

Merlin-engined Spitfires continued in production and service and operated increasingly in the fighter-bomber role, leaving the higher-performance Griffon-engined variants to deal with later and more advanced German fighters.

Spitfires served in the US Army Air Force (USAAF) from 1942. Two fighter groups were sent over to England and equipped initially with the Mark V, later transitioning to the Mark IX. In addition three so-called “Eagle Squadrons” of US pilots in RAF service would transfer to the USAAF in 1942, taking their Spitfires with them. An Eagle Squadron Spitfire is shown below.

USAAF units also used Spitfires in the Mediterranean theater until 1944, when they transitioned to the P-51 Mustang fighter. Interesting accounts of USAAF Spitfire operations may be found here and here. Below is shown a Spitfire Mark Vc in USAAF markings, which is preserved in the National Museum of the USAF. Note the sand filter beneath the nose and the desert camouflage – this is clearly intended to represent a Spitfire from the Mediterranean theater.

The Spitfire was somewhat hampered throughout its operational career by a relatively short range on internal fuel (400-500 miles at most). It had been designed that way, as a defensive fighter to protect Great Britain, and its range was adequate for that purpose. However, when different missions called for longer range, a solution had to be found. Adaptations included fitting the Spitfire with external drop tanks and modifying later versions to provide increased internal fuel capacity (particularly the photographic reconnaissance versions, some of which had a range of over 2,000 miles). However, it was never able to match the range of aircraft such as the P-51 Mustang, which (after an initial false start) was fitted with the Spitfire’s Merlin engine and developed into a long-range escort fighter to accompany USAAF bombers to their targets in Germany and back.

In order to allow the Spitfire to operate in support of the advancing Allied armies, Spitfire units were forward-based on improvised airstrips almost immediately following the D-day landings in June 1944. As the advance continued they moved to captured German airfields, and by 1945 were operating from within Germany itself. It was at this stage that another advantage of the wing-mounted external fuel tanks became apparent. Some ingenious armorer discovered that a keg of beer could be fastened in place of the drop tanks! The Heneger and Constable Brewery donated free beer, and Spitfires regularly made “maintenance flights” back to England, returning with two kegs beneath their wings. This is said to have led to frequent visits by USAAF fighters to RAF airfields, using all sorts of contrived excuses, as the USAAF apparently didn’t provide beer to their forward-deployed squadrons! (Allegedly His Majesty’s Customs And Excise Service were not amused and tried to stop the supply . . . but RAF Spitfire squadrons somehow, mysteriously, remained well-supplied with beer. I guess where there’s a will, there’s a way!) The painting below was commissioned by the brewery to commemorate the flights.

Spitfires also operated in the China-Burma-India theater with the RAF and in Australia and the South-West Pacific with the Royal Australian Air Force. Mark V Spitfires defended Darwin in northern Australia against Japanese air raids, and later Marks of Spitfires continued to drive the Japanese northward during General Macarthur’s campaign. Carrier versions of the Spitfire, known as the Seafire, operated in every theater of Royal Navy operations, including against Japan, and will be discussed in greater detail in the final instalment of this series next week.

Photographic Reconnaissance (PR) versions of the Spitfire were in service from 1939, as discussed in last week’s article. As new Marks of the fighter were developed the higher-performance versions were also produced in PR form. They were usually painted in a pale blue camouflage for high-altitude missions and in a strange pink color (which proved almost impossible to see against a background of low cloud or ground haze) for low-level work. Most had their weapons removed and the weapon bays in the wing converted to fuel tanks, plus additional fuel tanks in the fuselage and below it and the wings. This gave later models a range of about 2,000 miles.

PR Spitfires performed some of the most important and spectacular reconnaissance missions of the war, including the hazardous low-level operation that photographed the German Würzburg radar set at Bruneval in occupied France (shown below). This led to the famous Operation Biting in February 1942 to capture parts of it for analysis and its operators for interrogation.

They also conducted the famous reconnaissance of Peenemünde that led to its identification as the test center for German rocket development. This led to its destruction in Operation Hydra during August 1943. Below is the Spitfire photograph of Peenemünde in which V-2 rockets were first identified.

Spitfires also conducted regular reconnaissance of the Ruhr dams prior to their destruction in Operation Chastise during May 1943, and photographed them again the day after the raid to verify its results. One of the post-raid images is shown below. The pilot who took it later spoke of his experiences:

When I was about 150 miles from the Moehne dam I could see the industrial haze over the Ruhr area and what appeared to be a cloud to the east. On flying closer I saw that what had seemed to be cloud was the sun shining on the floodwaters.

I looked down into the deep valley which had seemed so peaceful three days before [on an earlier reconnaissance mission] but now it was a wide torrent.

The whole valley of the river was inundated with only patches of high ground and the tops of trees and church steeples showing above the flood. I was overcome by the immensity of it.

Merlin-engined PR Spitfire variants culminated in the PR Mark XI, shown in the video below.

The last PR version was the Griffon-engined Mark XIX, shown in the photograph and video below. It was based on the very successful Mark XIV fighter.

Next week, in the final instalment of this three-part series on the Spitfire, we’ll examine the Seafire naval variants, further development of the Spitfire into the Spiteful, Seafang and the jet-powered Attacker, and look at post-war production and service of this magnificent aircraft.

Peter