I don’t know whether many of my readers are familiar with the Skeleton Coast of Namibia. It’s a wonderfully desolate place, which I’ve visited three times, and of which I have very fond (and awed) memories.

The Skeleton Coast is famous (or, rather, notorious) among seafarers for its shallow patches, which undulate back and forth along the coast; for its incredibly thick fogs, which spring up when the icy cold waters of the Benguela Current off the coast chill the sea air, and it meets the hot air from the Namib Desert along the shoreline; and for its utter desolation . . . hundreds and hundreds of miles without habitation or any sign of civilization. It’s one of the world’s last unspoiled places.

It has rolling sand dunes and towering mountains; desert elephants, uniquely genetically adapted to their environment; wildlife found nowhere else on Earth; and plants that have adapted themselves to the harsh environment.

Navigation has always been hazardous along the Skeleton Coast, and countless ships have run aground there over the centuries. Some have disappeared beneath the shifting desert sands, never to be seen again. Others have been sucked far inland as the desert has expanded to seaward, so that today one finds shipwrecks miles from the sea.

Their crews – at least until the last century or so – were doomed. Cast ashore in so desolate a place, they had only themselves and their own resources to rely on. Countless thousands must have perished there, never to be seen again. These shattered lifeboat wrecks tell their own silent story.

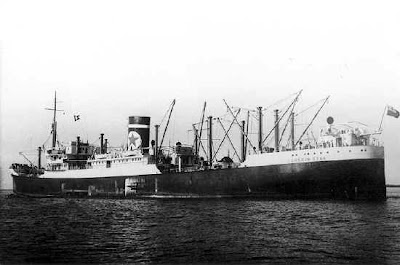

One of the more famous wrecks in recent times was that of the Dunedin Star.

She ran aground on the Skeleton Coast in 1942.

The mammoth rescue operation that unfolded included another wrecked ship, a crashed aircraft, and the need to rescue many of the rescuers! John Marsh wrote a famous book about it, now available via the Internet. Excellent reading.

The BBC reports that another shipwreck, lost for centuries beneath the sand of the Skeleton Coast, has been discovered. This one looks like an archaeologist’s dream!

A team of international archaeologists is working round the clock to rescue the wreck of what is thought to be a 16th Century Portuguese trading ship that lay undisturbed for hundreds of years off Namibia’s Atlantic coast.

The shipwreck, uncovered in an area drained for diamond mining, has revealed a cargo of metal cannonballs, chunks of wooden hull, imprints of swords, copper ingots and elephant tusks.

It was found in April when a crane driver from the diamond mining company Namdeb spotted some coins.

The project manager of the rescue excavation, Webber Ndoro, described the find as the “the most exciting archaeological discovery on the African continent in the past 100 years”.

“This is perhaps the largest find in terms of artefacts from a shipwreck in this part of the world,” he said.

The area is also known as the Skeleton Coast and is associated with the skeletons of wrecked ships and past stories of sailors wandering through the barren landscape in search of food and water.

Working out whose ship this was is no easy task.

Gold coins that the Portuguese crown began producing in October 1525 mean it could not have been the vessel of the famous seafarer Bartholomew Dias, who disappeared on one of his travels around the point of Africa in the year 1500.

But there are other pointers, including swivel-guns known to have been used by Portuguese and Spanish seafarers, and the boat’s shape, indicating that it was a Portuguese “nau”.

There are also copper ingots carrying a clearly visible trident seal that can be traced back to the German banker and merchant family of Jakob Fugger – the main suppliers of primary materials to the Portuguese crown.

Gold and silver coins have been deposited in a bank vault. Rare navigational instruments have been sent to Portugal for research, while pewter plates and jugs, pieces of ceramic, tin blocks and elephant tusks are temporarily housed in a warehouse on the premises of the mining company. Some are being freed of their layer of sand and salt to allow for more detailed scrutiny over their make and origin.

“It represents a very interesting cargo – we have goods from Asia, we have goods from Europe, we have goods from Africa,” said Mr Ndoro.

“We always think that globalisation started yesterday but in actual fact here we are with something we can date to around 1500.”

. . .

Bruno Werz, the archaeologist leading the excavations, said the shipwreck was particularly valuable because it had not been tampered with.

“This collection has not been disturbed by human interference,” he said.

“We are very fortunate to have found an untouched wreck with all the material that was on site still here in one collection.”

Archaeologists from South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, the United States, the UK and Portugal are working on the excavation, which is due to be completed by mid-October.

Thereafter the detailed work of recording and preserving, which can take up to 30 years, can begin.

This should prove to be a fascinating “time capsule” of shipboard life and international commerce in the 16th century. I’ll be watching with interest to see what else is revealed.

Peter

Very cool, I’ll have to read more about this place. Interesting quote on globalization–one could even say it started earlier, with the Silk Road trade route of the ancient Chinese, Persian, and Roman empires. Thanks for posting!