There’s an awful lot of hype circulating about breathing masks, respirators, and protection against the current coronavirus epidemic. Most of the articles are not scientific or factual – they’re more like hyperbole and hysteria.

In particular, current stocks of surgical masks and disposable respirators available to the general public have been largely exhausted, and a number of vendors are reporting that they don’t know when (or even whether) they’ll be able to get stock again. That’s complicated by the fact that most such masks are made in China, which last week was said to have declared them a “strategic national resource”. (I can’t find a first-hand report about that, only third-party references to it; but it sounds likely, under present circumstances.) Translation: they’ll be keeping all they can make, and won’t be exporting any for the foreseeable future. If true, that means serious trouble for institutions like hospitals, doctors’ and dentists’ surgeries, etc., who rely on them for basic medical hygiene as well as protection against infectious diseases.

The pity is, there’s no real need for such a shortage to exist. Surgical masks and respirators are not the first line of defense for the general public against coronavirus or any similar epidemic. There are many basic precautions we should observe to protect ourselves, such as this list from Dr. John Campbell (see the video from which it’s taken here – it contains useful information).

One may only need respirators when going out in public places, among people who may be infected with the disease. One doesn’t usually need them at home, or in the car, or most of the other places we find ourselves during the day. Coronavirus is transmitted by aerial droplets, which can settle on our skin, our clothes, and elsewhere; so not breathing them in at once is no real protection. If we handle our clothing, or touch our faces with hands that have touched our clothing, we’re basically at risk of infecting ourselves. (That’s why, for truly dangerous diseases such as ebola, medical personnel wear full-body hazardous material suits, full-face protection such as masks or goggles, respirators, etc., and tape up every seam between those garments and protective equipment. It can take more than half an hour to dress for the job, and as long to decontaminate and undress afterwards. There’s just no way you and I could ever afford to do that, even if the protective gear was available in sufficient quantity for everyone – which it’s not. Besides, it takes a trained team to help individuals suit up and disrobe; something most of us don’t have available.)

Still, respirators may serve a useful purpose if things get to the point that the virus is widespread and infection more likely. If we have to go to the supermarket to buy food, sure, it’s a useful layer of protection on top of common-sense precautions (of which more later). However, that presupposes that when we get home from such tasks, we strip off our clothing and wash it, take a shower to clean ourselves, and observe basic anti-infection precautions at all times. What’s more, replacement respirators are not likely to be available anytime soon; so we daren’t waste what we’ve got. Some have suggested wearing a surgical mask over the respirator, to catch initial droplets, dirt, etc. and prevent them from reaching the respirator. That may be a good idea; I simply can’t say.

Let’s distinguish between the two, for a start. A surgical mask (shown below – image courtesy of Wikipedia) is what we see staff wearing in hospital surgery areas and intensive care units almost every day.

It’s designed to filter what we breathe out, to prevent us infecting others if we happen to be carrying something like a cold or the flu – or coronavirus, for that matter – as well as keep splashes of fluid like blood, etc. from entering the mouth or nose of medical personnel. Its secondary job – at which it’s not very efficient, but better than nothing – is to stop infectious droplets, viruses, etc. from entering our mouth or nose. Furthermore, it’s relatively easy to breathe while wearing a surgical mask. They’re currently recommended by some governments as being more appropriate for use by the general public than respirator masks.

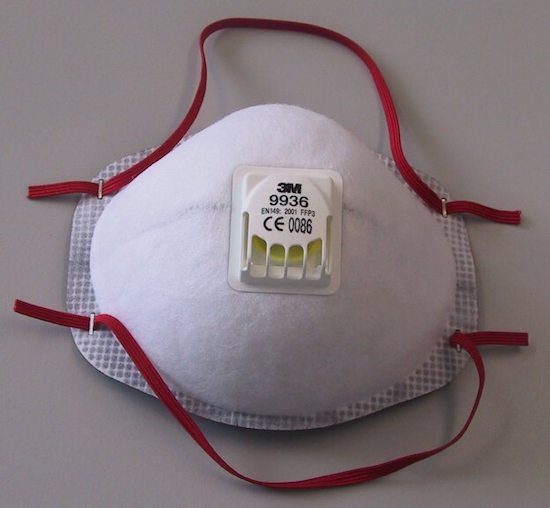

A dust mask or disposable respirator (shown below, ditto Wikipedia) is more efficient at keeping out external pollutants and infectious material, but isn’t a perfect seal, meaning that such hazards may still gain access to our mouth and/or nose by seeping in underneath the edges of the mask.

One used to be able to get these at hardware stores, paint counters, etc., but they’re very hard to find at present. It’s usually harder to breathe freely and easily when wearing such masks, if they’re properly fitted to our face.

A half-face or full-face respirator is another matter entirely. These masks typically require careful fitting, and operators need to be trained how to put them on and use them effectively. This usually involves a respirator fit test to ensure they’re working correctly. (Beards and mustaches can be problematic when wearing a respirator, preventing the unit from sealing to the face. They may have to be trimmed or even shaved off, particularly if they’re very long or thick.)

Because respirators are “professional grade” (or at least claim to be), it’s usually easier to breathe when wearing them than when using a disposable dust-mask-style respirator. Half-face respirators protect the mouth and nose. The one shown below is the GVS SPR457 Elipse P100 Dust Half Mask Respirator, which I prefer, because it seals well even if one has facial hair, as I do – many respirators don’t. (It’s very useful to protect against general dust while cleaning, sawdust, smoke from wildfires, and a host of other annoyances. I’m a cardiac survivor, a former smoker, and an older man; so, with a “triple whammy” like that stacked against me, I need to look after my lungs. This does a good job.)

Full-face respirators add goggles or a mask to protect almost the entire face. Of course, one can add safety goggles or a face-mask shield to a half-face respirator to obtain almost the same level of protection as that offered by a full-face unit. There’s no point in going overboard, though; ordinary folks like us simply don’t have access to the full-body medical protective gear needed to provide security against infection, and we lack the training needed to use it properly and effectively. For our purposes and needs, a half-face respirator is likely more useful and cost-effective than the full-face version.

When should we use what type of breathing protection? Wikipedia sums up the professional recommendations as follows.

Surgical Masks are primarily intended to protect the wearer from direct splashes and sprays of blood and bodily fluid as well as the release of aerosols from the wearer that may adversely impact a patient or other individual. N95 filtering facepiece respirators cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use as surgical masks, in addition to providing respiratory protection to the wearer, are known as Surgical N95. Typical surgical masks do not provide the same level of filtration as a NIOSH approved respirator as they are neither tight-fitting or capable of providing sufficient filtration over a wide range of particle sizes. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of surgical masks as part of standard precautions when conducting procedures that result in aerosol generation and the patient is not anticipated to be infected with a disease known to be transmitted by small aerosols. The CDC recommends the use of NIOSH certified respirators equivalent to N-95 or greater to prevent the inhalation of infectious particles (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Avian influenza, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), pandemic influenza, and Ebola.)

What about the ratings? We hear the number N95 bandied around quite a lot. There are three letter grades of respirator – N, R and P – and three levels of protection – 95, 99 and 100. They work like this (note that the text below refers to proper half- or full-face respirators, not dust masks or surgical masks).

N-Series (N95, N99 and N100)

N-Series particulate respirators are NOT resistant to oil and therefore provide protection against solid and liquid aerosol particulates that do NOT contain oil. Examples of common non-oil based solid particulates include “dust” particles related to coal, iron ore, flour, metal, wood and pollen and non-oil based liquids. The difference between an N95, N99 and N100 respirator is simply the filter’s efficiency level (i.e. N95 = NOT Resistant to solids and liquids which contain oil and provides 95% efficiency). The higher the efficiency, the more particulates the respirator will filter out. Of these three efficiency levels, the N95 is the commonly used. It is important to note that N-Series respirators have a non-specific service life, and can be used as long as the mask is not damaged or breathing resistances are not detected.

R-Series (R95)

Unlike the N-Series, the R-Series particulate respirators are resistant to oil, which means they provide protection against both solid and liquid aerosol particulates that may contain oil. R-series respirators, however, are only certified for up to 8 hours of service life. Due to these specific service life restrictions, R-Series particulate respirators are the least common type of particulate respirators.

P-Series (P95 & P100)

P-Series particulate respirators are similar to the R-series in that they provide protection against both solid and liquid aerosol particulates that may contain oil. The service life of P-Series particulate respirators, however, is substantially longer, with NIOSH recommended disposal after 40 hours or 30 days of use, whichever comes first. This extended service life is contingent on the mask being undamaged with no detectable breathing resistances.

You’ll note that the GVS half-face mask I use is rated at P100. There is no higher respirator rating, so I have confidence in the protection it provides. (The manufacturer confirms that it’s rated by NIOSH as protection against “micro-organisms, i.e. bacteria and viruses”.) Its replaceable filters appear expensive at first glance, but they actually work out to be fairly economical compared to the cost of buying (currently very expensive) disposable N95 dust masks for the same period. I keep spares on hand, and recently bought more, in case they may not be available when I need them.

(EDITED TO ADD: You can also get disposable respirators. These are not particularly economical, because they’re discarded after use – at least, that’s what’s supposed to happen. In reality, I know folks who’ve used them over several days, keeping them clean during and in between uses. I keep a couple in the car, in case we have to drive through heavy smoke or anything like that. In the absence of anything better – particularly if you can’t buy regular respirators – they have their place in our emergency planning.)

I hope this helps clarify the situation. There’s an awful lot of bad information out there. It behooves us to do our homework, and not spread false rumors.

Peter

Thank you for the good overview of the situation.

The Powers That Be keep insisting that a beard can't get a seal, so shaving is required… I have been able to pass respirator fit testing (when they allow it) with a beard. Last year I used a positive pressure air supplied SCBA system and shocked the trainers by making it work with a full beard.

I think the best defense will be good hygiene and social distancing. Do you have any thoughts on diet and medical system quality influencing mortality rate? I've read some people who claim that China will see a higher mortality rate than the West due to worse healthcare and diet, but the big cities I'm familiar with in China seem to have fairly good healthcare and diet, so I'm skeptical of the claims.

As an aside:

I used to be the OC (pepper spray) trainer where I worked prior to retirement.

Through experimentation I discovered that a N95 mask would allow a person to enter an OC contaminated room and handle a person contaminated with OC with no discomfort. We were using OC suspended in water.. I did not test this using OC in an oil suspension (we stopped using oil suspended OC due to people who had been sprayed and then subsequently hit with a Tazer which set them on fire).

Good information.

I chose the 3M Rugged Comfort Quick Latch Half Facepiece Reusable Respirator 6502QL.

I use it for woodworking dusts, cleaning where there are dusts and/or mold, painting, and hobby welding.

Note that the best protection is when the cartridge is matched to the use.

I also bought the 3M Rugged Comfort Quick Latch Half Facepiece Reusable Respirator 6502QL.

All the filters fit both the half face and full face respirators.

I prefer the full face for the rare times when I'm using Muriatic acid, and those times when I'm using a diamond wheel for stone work.

All the respirators are available in a range of sizes, and yes, they have to fit right to be of use.