Readers may be familiar with the Australian writer Russell Braddon. He was a prisoner of war of the Japanese from 1942-1945, and suffered greatly on the infamous Burma Railway project. Out of that experience came his best-known book, ‘The Naked Island‘, chronicling his experiences as a POW. He followed it some years later with a sequel, ‘End Of A Hate‘, describing his homecoming to Australia and readjustment to life in civilization. I read both books as a youth, and recommend them very highly, ‘The Naked Island’ in particular: it’s one of the finest and most grippingly brutal accounts of what it meant to be a prisoner of Japan during World War II. (If you’d like to read more about how the war affected Mr. Braddon and led him into a writing career, there’s an excellent short article about it here in Adobe Acrobat [.PDF] format. Interesting and recommended reading for all veterans who’ve had to adjust to life after gruelling experiences in the field or in captivity.)

I was therefore interested to read of the death of another survivor of the Burma Railway project, a man who – despite ingrained hatred and bitterness – wrote about his experiences in captivity, and was able to bring himself to forgive his captors. His obituary in the Telegraph tells the story.

Eric Lomax, who has died aged 93, long nursed thoughts of revenge on his wartime Japanese captors then, in his dotage, finally had the chance to act when he came face to face with his principal tormentor; his choice of reconciliation over retribution inspired both those who met him and a film now being made starring Colin Firth.

A Signals officer captured at Singapore in 1942, Lomax was a prisoner at Kanchanaburi camp in Thailand when guards found a radio receiver, and a map he had made of the Burma-Siam “death railway”.

He was made to stand for long hours in the burning sun. Stamped on, he had his arms broken and his ribs cracked with pickaxe handles; later he was waterboarded, with his head covered and water pumped into his nose and mouth to make him feel as if he was drowning. At night he was confined, coated in his own excrement, to a cage. A doctor who examined him later said there was not a patch of unbruised skin visible between his shoulders and his knees.

During his torture, Lomax’s English-speaking interpreter repeatedly demanded he confess to espionage, saying: “Lomax, you will tell us …” and adding “Lomax, you will be killed shortly.” Knowing that an admission would seal his fate, Lomax remained steadfast. Such were the tortures inflicted upon him that he remembered calling out for his mother; but there were moments, too, when he was questioned about his schooling. At the last, when it became apparent he would not be executed, he was told, in a parody of English manners, to “keep your chin up”.

. . .

Lomax’s loving second marriage to Patti Wallace in 1983 also came under stress, as she faced his immense stubbornness, which could suddenly switch to outright hostility so that he would refuse to speak to her for a week. Eventually she wrote to a doctor studying PoWs’ psychological problems, and he read in The Daily Telegraph about the recently-formed Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, which he started to visit.

A fellow former-prisoner then gave him a cutting from the Japan Times about a ex-Japanese soldier who had been helping the Allies to find the graves of their dead and claimed that he had earned their forgiveness. The accompanying photograph showed Takashi Nagase, the interpreter during Lomax’s interrogation, and the man with whom he most associated his ordeal.

For two years Lomax did nothing. Then he obtained a translation of Nagase’s memoir, which explained how shame had led the interpreter to create a Buddhist shrine beside the death railway. Patti Lomax then wrote to Nagase, enclosing her husband’s photograph and suggesting that perhaps the two men could correspond. She asked: “How can you feel ‘forgiven’, Mr Nagase, if this particular Far Eastern prisoner-of-war has not yet forgiven you?”

The reply she received declared: “The dagger of your letter thrusted me into my heart to the bottom.” Nagase admitted that he still had flashbacks about torturing Lomax and thanked her for looking after her husband until they could meet. When Patti Lomax wrote back she enclosed a formal letter from her husband. Eventually the two elderly enemies arranged a meeting.

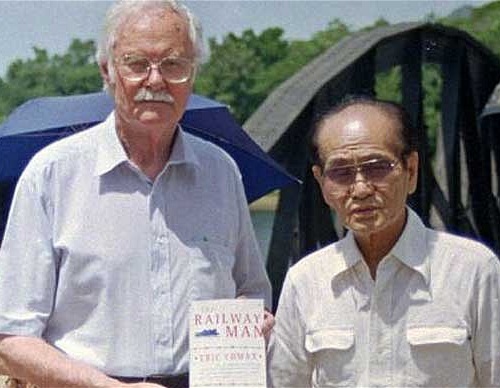

More than half a century after their previous meeting, the two men approached each other on the bridge on the river Kwai. After bowing formally, Nagase nervously acknowledged that the Japanese Imperial Army had treated the British appallingly. Lomax found himself saying: “We both survived”. Later Nagase said: “I think I can die safely now”. When they next met, in a Tokyo hotel room, Lomax carefully read out a letter he had written assuring Nagase of his total forgiveness.

. . .

His meeting with Nagase was filmed for a television documentary, Prisoners of Time (1995), in which he was played for other scenes by John Hurt. It was broadcast on the 50th anniversary of V-J Day. The following year Lomax published The Railway Man, a powerful memoir placing his wartime experience in the context of his whole life. It won the JR Ackerley Prize and the NCR book award, and prompted other former Japanese prisoners to write from all around the world.

In 2007 Osamu Komai, the son of Mitsuo Komai, the second-in-command at Kanchanaburi camp who was hanged after the war largely on Lomax’s evidence, visited Lomax at his cottage in Berwick-upon-Tweed to apologise for his father’s actions. Their conversation, conducted through an interpreter, was filmed for a Japanese television documentary.

Afterwards Komai seemed relieved. “Apparently it was the equivalent of offering me his soul,” Lomax said.

Disgusted by his own wartime actions, Takashi Nagase considered suicide after the war, but instead opened an English language school. He married, then began making pilgrimages to Kanchanaburi. Back in Japan he started making speeches promoting reconciliation between former Japanese soldiers and Allied prisoners. He persevered despite a hostile reception from many of his countrymen, and in 1976 introduced 23 ex-PoWs to 51 former Japanese soldiers at Kanchanaburi. In October 1989 Lomax read Nagase’s memoir Crosses and Tigers, which described how the interpreter was still haunted by the brutal torture of one particular prisoner. “That prisoner was me,” Lomax said. The film of their story, also called The Railway Man, is due out next year.

There’s more at the link. Recommended reading.

I’ve always taken a special interest in the POW’s captured at Singapore, and what happened to them, because but for the vagaries of fate, my father might have been among them. In Weekend Wings #9, which examined his life, I wrote:

Within weeks after [his] wedding he was posted overseas. His intended destination was Singapore, but he was taken off the troopship at Durban in South Africa to help deal with an urgent engineering problem on Beaufort torpedo-bombers being assembled there for use by the South African Air Force. The rest of his convoy went on to Singapore, where all its troops were captured by the Japanese in early 1942. Dad always reckoned that some Guardian Angel had been looking out for him, because only about three out of every ten of that draft came home after the war. The rest died in Japanese prison camps.

With that in mind, I found it very moving to read of Mr. Lomax’s experiences. I’ll have to read his book, I think. Fortunately, it’s still in print, and even available as an e-book. I hope the forthcoming film is true to his experiences, and not overly ‘Hollywood-ized’.

May his soul, and the souls of all who suffered and died during and after that dreadful experience, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

Peter

Hi Peter,

I also spoke with a person that was a "guest of the Emperor of Japan"

Glenn Frazier was a survivor of the Bataan Death March and I met him at a book signing.

Here is the story

http://mydailykona.blogspot.com/2012/09/busy-week.html

I am still in awe of those that survived where soo many did not.

I thought I recognized Takashi Nagase. He was also in "To End All Wars" which was written by Ernie Gordon, a POW building the same railway. An amazing tale of brutality and the forgiveness of same.

Wow. Just wow.

I worked with a man who, as a child, was a Dutch civilian detainee of the Japanese during WWII. His experience was trivial compared to the military captives, but he still detested the Japanese so much after over 40 years that he refused to buy Japanese products.

Japan's treatment of its prisoners, both civilian and military, during WWII was truly shameful. Forgive, but don't forget.

When i was at boarding school in the 1960s we had a maths teacher who had been a prisoner of the Japs and who had some strange ways of acting of course all the boys took the mick mercilessly until on a very very hot summer day over a weekend we saw him with his shirt off his back was a mass of scars he had been whipped with a cat of nine tails each bound with barrbed wire,we stopped the micky taking after that.God knows what else he went through.

Many years ago, Nevil Shute wrote a novel called A Town Like Alice, or The Legacy, which described a small part of the Bataan Death March. I have been interested ever since. I have always somehow connected Vietnam with that event. Thanks for brining this up. These books look really interesting.