April 6th is a sad day in US law enforcement history. On that date in 1970 the so-called Newhall Massacre took place, when four California Highway Patrol officers were killed by two criminals.

The felons were military veterans who were well-trained in the use of firearms (and were on their way back from a range practice session when the incident occurred). They carried far more firearms than the officers, and had agreed among themselves to fight rather than submit to arrest and practised their moves in such a situation.

The officers, on the other hand, while being military veterans themselves, had what proved to be inadequate law enforcement training and made several tactical mistakes that contributed to their deaths. After the Newhall incident law enforcement training across the US was significantly improved, incorporating many “lessons learned” from Newhall.

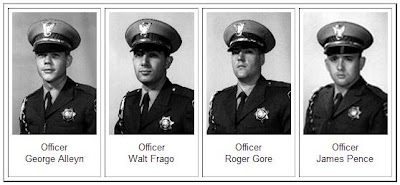

May Officers George Alleyn, Walt Frago, Roger Gore and James Pence rest in peace.

The troubling thing is, in today’s technology-driven world we’re seeing far too much emphasis on tools and not enough on tactics in many law enforcement academies. I’m sure many readers have seen news reports that police are “outgunned on the streets” by criminals with “assault weapons”. This is usually not the case – most modern police departments deploy handguns, shotguns and semi- or fully-automatic rifles. The problem is the use of those weapons. It’s not enough to train on a square range where the targets don’t shoot back. One has to train in fire and movement, urban guerilla warfare tactics and so on – and far too many police departments aren’t doing that yet, or aren’t reinforcing initial training with ongoing practice.

Furthermore, individual officers (or small numbers of them) should not be trying to charge in where angels fear to tread. Unfortunately, too many police departments have reduced their staff numbers to such an extent that only one or two officers may be available to respond to an incident, and find themselves facing really serious opposition. Once more, training needs to emphasize calling for backup when necessary and using numbers intelligently to reduce the risk.

The threat is particularly worrying in the light of the large number of gangsters joining the US military in order to receive advanced training in weapons and tactics and pass it on to their “homies” when they get out. We hear talk of the “Zetas” and similar units serving Mexican drug cartels, but the same threat is now a reality on many US inner-city streets. The television news report below is only one of many like it in the print and broadcast media that have highlighted this problem.

I’ve spoken with friends at local military installations (including one of the major training centers preparing soldiers for overseas deployment) and they confirm that the problem is real and growing. With the need to recruit additional personnel for an expanding military, sometimes standards are allowed to slip a little, and individuals who shouldn’t be allowed to enlist are getting through the net. If their instructors have seen this and are worried about it, how much more should we citizens be worried?

It reinforces what I tell my students when I teach firearms safety and use: a firearm may save your life, but it’s not the Hammer of Thor rendering you invulnerable, invincible and infallible. Sure, carry a firearm for personal safety after obtaining the appropriate permit; sure, have a firearm ready to defend your home and loved ones; but the smartest solution is not to go into places where you might have to use it, and retreat rather than play Macho Man and refuse to back down in the face of a threat. You may well defeat the threat, but the legal expenses of proving you were in the right, and fighting lawsuits from the bad guy and/or his family, and perhaps recovering from injuries you sustain in the process, will soon teach you that discretion is the better part of valor. The use of deadly force is a last resort when all else has failed, not a primary option.

The four police officers who died at Newhall were killed by criminals skilled in the use of weapons who used better tactics than their opponents. There’s no guarantee that citizens like ourselves won’t face a similar problem. Keep that in mind, and as we honor their memory (and thank them for the improvements in law enforcement training that resulted from their deaths) let’s improve our own situational awareness, defensive training and preparedness accordingly.

That will be the most fitting and lasting memorial to the fallen.

Peter

In Iraq when our guys meet heavy opposing firepower they call in Hellfires (and D*mnation) on they enemy. We’re not there yet.

Chilling.

I realize you’re discussing different topics–you’re talking about individual situations, whereas he is discussing policing in general–but you and LawDog have managed an interesting juxtaposition of thought today.

He’s talking about Peel’s principles and avoiding force, and you’re advocating training “in fire and movement, urban guerilla warfare tactics and so on.”

Again, I know you’re discussing training for the individual case that requires it, and not advocating it as a day-to-day practice, but it’s interesting, especially given the tendency of people to feel the need to use their training–when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

How do you reconcile the two?

Actually, Dave, there’s no conflict at all between Lawdog’s points and mine. He’s talking about the function of police in society – in which I entirely agree with him, of course. I’m talking about the dangers faced by police in the course of the exercise of that function: dangers which confront all of us as citizens, not just those of us wearing a badge.

I firmly believe that every, repeat, every responsible citizen should get at least basic training in how to respond to a defensive emergency. For those who are able and willing to expend the time and money necessary, more advanced training is highly recommended. If our enemies, the criminals, are doing the latter, isn’t it only common sense for us to do likewise? And for those to whom we entrust the function of maintaining law and order in society, it’s not just common sense, it’s vital!

That doesn’t mean that police (or citizens) walk around strapped to the nines, glowering at everyone in the vicinity and ready to whip out a weapon and spray down the neighborhood at the slightest provocation. It simply means we recognize the threat and are ready to deal with it as best we can.

I think Sir Robert Peel would approve.

Perhaps I phrased the question poorly. I agree with you that it’s important to be prepared to deal with such unsavory elements, and I take steps myself (as a private citizen) to prepare–I attend some kind of training at least once a year, and typically more (usually a weekend course annually, and a 4-hr evening course once or twice over the course of the year).

As a private citizen, I’m free to do that with my own money, but we’ve all seen the political process at work: when the officers are training on the public dime, they have an incentive to show that those training dollars were spent wisely. Thus, we end up with the overuse of tactical teams.

What would you do to ensure our officers get the training they need, but are not put in a position (psychological or political) to use that training unnecessarily?

Good question, Dave, and I don’t know the answer. So much of it devolves to “common sense” – an uncommon commodity these days! I suspect that if the top leadership of a law enforcement organization are “on the ball” there’ll be few problems. However, if that top leadership focuses more on politics than policing, the outlook is bleak.

*Sigh*