Today’s snippet comes from one of the most unusual submarine warfare memoirs of World War II.

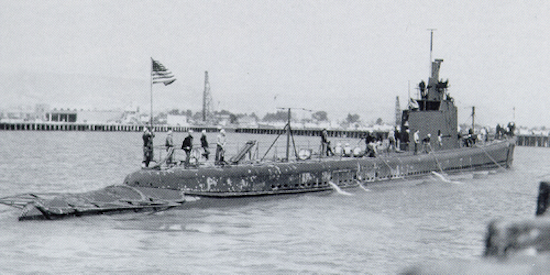

Forest J. Sterling was a (or, rather, the) Yeoman aboard USS Wahoo (shown below), one of the most successful submarines in the US Navy during the war against Japan.

Sterling’s job was to take care of correspondence and administrative paperwork for the Captain and officers. He made several war patrols under her most successful commanding officer, Cdr. Dudley “Mush” Morton, who became a living legend in the submarine service before his (and his ship’s) untimely demise.

Sterling wrote the classic book “Wake of the Wahoo” about his service aboard the ship.

It’s one of the finest combat memoirs I’ve read by any enlisted sailor from the period. I could select almost any chapter to quote here, but I thought an explanation of how Sterling survived Wahoo’s last war patrol might interest you. Without a great deal of luck and the consideration of her skipper, he would have died with the rest of the crew.

The story begins in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, before the ship sailed. The crew had just rejoined the ship after a period of liberty ashore.

The relief yeoman had opened the mail, taken care of the most important business, and left the rest for me. Thumbing through the correspondence hurriedly I saw my name. I picked out the letter and scanned it hurriedly. Letting out a war whoop that could be heard the length of the ship, I rushed to the wardroom. Captain Morton and the Executive Officer were discussing a serious problem.

“Captain! ComServPac has approved my request for Steno School, sir.” I showed the two officers the authorization for my transfer. I was trembling with excitement.

The Captain looked at the order uncomprehendingly. Then his eyes lighted up. “That’s great news, Yeo.” He studied the order a second longer and added, “Your class convenes 1 November, that right, Yeo?”

“Yes sir.”

He turned and looked at me squarely. “Yeo, I’m going to ask a favor of you.”

My heart sank within me. “Yes sir.”

“Howsabout you making one more patrol with me? We’ll be back in October. When we get in, I’ll get you plane transportation back to the States. You might miss out on some leave, but you had thirty days in June. How about it?”

I said, “Captain, your word is good enough for me. I’ll get back to work.”

He grinned at me. “Thanks, Yeo. I knew you wouldn’t let me down.”

So Sterling sailed on Wahoo’s seventh (and, as it would turn out, final) war patrol. The ship went first to Midway Atoll, over a thousand nautical miles closer to the operational area than Pearl Harbor, to refuel and replenish supplies, which would allow her to stay longer on patrol. The story continues in Midway lagoon.

I went below and got a copy of the sailing list … I date-stamped it 13 September 1943, placed it in an envelope, and rolled it partway into the typewriter.

Going back to the messroom, I got a cup of coffee and asked Bailey where Rennels was.

“He’s topside looking at the gooney birds.”

I took my coffee topside and found Rennels looking towards Midway Island. I said, “Boy, you look as gloomy as I feel.”

He said, “Yeo, I got a terrible feeling that something is going to happen to us this trip.”

“Aw, snap out of it. I feel bad, too, but nothing’s going to happen to Wahoo while I’m on here and don’t you forget it.”

He grinned. “Yeah, you been feeding that old baloney to all the crew, but this is Jack you’re trying to kid.”

His nose began to twitch and he looked around. He walked to the rail and blew his nose. Then he gave his fingers a flip, and I saw something yellow go spinning over the side. He threw his leg over the steel cable life line and I thought he was going to dive overboard.

“What is it, Jack?” I cried, alarmed and sprang to catch him. He pulled back and we stared at widening ripples in the water.

He said resignedly, “Now I know something bad is going to happen. I just lost the ruby ring that Lottie gave me when I was home.”

We stared for a minute at the water. “It was large for my finger. I meant to get it cut down before we left Pearl and forgot to,” he added.

There did not seem much to say after that, and we just stood on deck watching the birds. The sky was overcast and the weather misty but the sight of land, even Midway, was good.

Finally Rennels said, “Well, I gotta get noon chow ready,” and he went below decks.

After chow I wandered topside again. I noticed a number of men topside. They were strangely subdued. Few words were spoken. I could feel restlessness in every attitude.

Two or three Sperry men and several Wahoo men were topping off fuel from a line that ran along the dock and was being valved into a metal-jointed tube that was attached to a connection on Wahoo’s deck. Jacobs and Garman were overseeing the job.

Jacobs walked up to me, wiping oily hands on a rag he had taken from his hip pocket. He shook his head lugubriously. “I have a feeling that we’re going to catch hell this trip out.”

I said, “Forget it, Jake. The only thing that will catch hell will be the Japs. How’s the wife and that prospective baby doing?”

He brightened. “Last letter I got, the wife told me not to worry none. They’re just fine.”

“That’s fine. Another trip or two and you’ll be back there bouncing him on your knees or whatever you do with newborn kids.”

He shook his head. “I hope so.”

Something got his attention and he hurried over to the fuel hose connection. There was a strong smell of diesel fuel in the air. They finished fueling and the hose was passed over and secured to the dock. I looked at my watch and it was 1430. I took another look around. The weather was getting drizzly, and I went below to the office. I sat down in the chair with my back to the door, cocked one foot up on a corner of the desk, and leaned back smoking. I wondered what Marie was doing. It would be about five or six hours later in Los Angeles. I heard someone coming through the door behind me, and the Captain’s flat hand nearly slapped me off the seat. Turning, I said grouchily, “You nearly made me swallow my cigarette, Captain.”

He was in a jovial good mood. “Got your orders made up, Yeo?” he asked, teasingly.

“No sir, Captain, but I could sure make them up in a damn quick hurry if you gave me the word.”

He added, more serious, “We’ve got an hour before we sail. Let’s go up to the Squadron and get you a relief.”

I could hardly believe what he was saying. “If you mean it, Captain, what we waiting for?”

He laughed heartily. “Come on.”

We went topside and over the gangway together. I crawled into a jeep with him, and he drove along the dock recklessly. I still thought he was joking, and that when we got there, I would find a clerical job that needed attending to.

I went trailing behind him up the officers’ gangway and into the Squadron Office. I followed him to the Squadron Commander’s desk. Captain Morton said, “I’m giving up the best Goddam yeoman I ever had working for me. He’s got orders to go back to Stenography School. I say there’s nothing but the best for the best. Have you got a relief you can give me for him?”

Blushing, I turned around and saw that all hands were staring at me. Captain Morton’s words were so loud I was sure they could be heard throughout the ship. At the same time I took on a swagger and threw out my chest with pride. I had been complimented by the best submarine Skipper in the Submarine Fleet.

The Squadron Commander looked up, laughing. “I think it can be arranged, Mush.” There was admiration in his voice. He called to three yeomen in white jumpers. They came quickly over and I noticed second-class chevrons on all of them.

Captain Morton said to me, “Which one is the best, Yeo?”

I answered, “Sir, I don’t know which is the best, but this man here wants the Wahoo more than anybody else.” I pointed at White. “He did a damn good job as relief yeoman on the Wahoo when we were at Goon – I mean Midway before, sir.”

Morton said, “That’s good enough for me.” He turned to the Squadron Commander. “What do we do now? I’m sailing in forty-five minutes.”

The Squadron Commander said, “We’ll have White over there in half an hour. You tell your yeoman to make his orders out, ‘Transferred by verbal orders, Squadron Commander’.”

Morton said, “Come on, Yeo, let’s get moving.”

Everything was happening so fast I could hardly keep up with the train of events.

Back on the Wahoo I quickly typed out my orders and record papers. Lieutenant Commander Skijonsby was very pleasant when he signed my papers. I ran through the ship to my locker and stuffed my sea bag with belongings. In the messroom the crew gathered around me enviously. “Yeo, when you get back to the States look up my wife and say hello for me.” “Yeo, hows to drop in on my mother…” “Here’s a note to my dad in…” I stuffed the addresses and notes in a shirt pocket.

I shook hands and said, “So long, be seeing you Stateside,” to Phillips. He said, “I hope so, Yeo.” He looked pale. I felt as though I had let him down.

O’Brien came in with, “Some guys sure do have a drag. Who did you bang ears with this time?”

I said, “I don’t know, but if I get a chance I’ll bang ears with them again.”

“Howsabout a game of acey-deucey, Yeo, before you go? You got time and I’d like to beat you just once more,” O’Brien said.

“To hell with you. You’re trying to get me tied up so I’ll be to sea before I realize it.”

A change came into O’Brien’s voice and he said quietly, “Yeo, here’s my wife’s address. When you get back, look her up and tell her I’ll be home for Christmas.”

I said, “Sure, O’B, sure thing.”

Rennels went topside with me. The Executive Officer had asked me to take the sailing list over with me, and I had it, my orders, and records in hand. Rennels carried my sea bag topside in the old Navy custom. We shook hands, and he went below decks.

Maneuvering watch was stationed and I remained near the gangway. At precisely 1556, a jeep raced up to the gangway and White came on board. The officers were on the bridge, and I could see Gerlacher, with the earphones I had worn so often in the past year, looking down at me from the bridge.

I hastily scratched my name off the sailing list and scribbled White’s name and address, somewhere in the New England states, in my place. Then I saluted the Colors and Kemp the Deck Watch and crossed over to the pier.

The jeep driver was waiting to take me to the Sperry. I told him to go on back, that I would walk.

Standing on the dock with six or eight line handlers from the Sperry, I watched them single-up the lines, heard the diesels come to life, and helped push the gangway in towards Wahoo’s deck. Then there was just the bowline left, and when the Captain ordered it thrown off, I pushed the line handlers away and pulled the bight clear of the bollard and heaved it into the water. Wahoo’s fog horn sounded a loud parting blast and a whistle on the bridge sounded shrilly. I watched Wach take down the Union Jack. Out of the corner of my eye I saw the Stars and Stripes on the cigarette deck as they furled out. Wahoo drifted away from the pier and began to move away slowly.

Captain Morton’s voice came across the widening water. “Take care of yourself, Yeo.”

“Good hunting,” I shouted back. I waved at everyone I could see topside. All were waving and grinning as Wahoo pulled away.

When I looked around, the line handlers were near the other end of the pier walking back toward the Sperry. I threw my sea bag on the rough planks and sat down on it. I lighted several cigarettes and smoked them before Wahoo, a tiny submarine silhouette on the horizon, headed into a rain squall and disappeared from sight. Forever.

According to Wikipedia:

Wahoo got underway from Pearl Harbor, topped off fuel and supplies at Midway on 13 September, and headed for La Perouse Strait. The plan was to enter the Sea of Japan first, on or about 20 September, with Sawfish following by a few days. At sunset on 21 October, Wahoo was supposed to leave her assigned area, south of the 43rd parallel, and head for home. She was instructed to report by radio after she passed through the Kurils. Nothing further was ever heard from Wahoo.

On 25 September 1943 the Taiko Maru was torpedoed in the Sea of Japan; mistakenly credited to the USS Pompano (SS-181), it was apparently sunk by Wahoo.

On 5 October, the Japanese news agency Domei announced to the world that a steamer, the 8,000 long tons (8,100 t) Konron Maru, was sunk by an American submarine off the west coast of Honshū near Tsushima Strait, with the loss of 544 lives. The victims included two Japanese congressmen of House of Representatives, Choichi Kato and Keishiro Sukekawa. Postwar reckoning by JANAC showed Wahoo sank three other ships for 5,300 tons, making a patrol total of four ships of about 13,000 long tons. The sinking of Konron Maru enraged the Japanese navy, and the Maizuru Naval District ordered a ‘search and destroy’ operation for US submarines.

Japanese records also reported that on 11 October, the date Wahoo was due to exit through La Pérouse Strait in the morning, Wahoo was bombarded from Cape Sōya. An antisubmarine aircraft (accurately Jake) sighted a wake and an apparent oil slick from a submerged submarine. The Japanese initiated a combined air and sea attack with numerous bombs and depth charges throughout the day. Sawfish had been depth-charged by a patrol boat while transiting the strait two days before, and the enemy’s antisubmarine forces were on the alert; their attacks fatally holed Wahoo, and she sank with all hands.

It’s only due to Cdr. Morton’s last-minute change of heart that Forest Sterling survived. He went on to retire from the Navy as a Chief Yeoman in 1956. He published his book in 1960.

In an epilogue to a later edition of his book, Sterling wrote:

After finishing stenography school, I was transferred to USS Comet (AP-166), and was at the initial landings of Saipan, Tinian, Guam and Leyte before being returned to submarine duty at Pearl Harbor.

As of the writing of this epilogue, June 1997, I am a resident at the United States Naval Home in Gulfport, Mississippi. At midnight, January 1, 2000, in keeping with my predictions to my Wahoo shipmates, I expect to hoist a few beers and say to them: “Sorry, fellows, I should have been with you. I can never understand why Captain Morton changed his mind and transferred me at the last moment. My spirit has been with you all these years!”

The rest of the crew of the Wahoo are still on “eternal patrol“. Her wreck was identified and photographed in 2006.

Peter

EDITED TO ADD: If you can’t get hold of Forest Sterling’s book at an affordable price, another excellent work about the ship is by Richard O’Kane, former Executive Officer of the Wahoo and later Commanding Officer of USS Tang. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, among others, for his World War II service. His book is titled “Wahoo: The Patrols of America’s Most Famous World War II Submarine“.

He wrote another volume, “Clear The Bridge! The War Patrols of the USS Tang“, about his later service.

Both books are outstanding in their field, and well worth reading.

Thank you for that.

Glenn SSBN609bAGSS555, SSN595.

Someone had to live to tell the tale. It's a mixed blessing.

Ouch! I naturally went to Amazon to buy the book, and they had it in stock. Alas, $51 for the paperback. So I zipped over to http://www.alibris.com, cheapest used copy was $37. Have to try to get it when the library re-opens.

Helluva book. And yes, 'somebody' guided the hand that kept him ashore. RIP CDR Morton and crew, the Navy has the watch.

@John Cunningham: See my addition at the foot of the article, giving two other books (available at much lower prices) that you might enjoy.

I went to the Wikipedia link to the Sperry (AS-12). There the picture of the Sperry showed the Dixon (AS-37) in the background moored at Ballast Point where I was stationed on the Nereus (AS-17). Before that, I was stationed in Guam on the Proteus (AS-19) shown between the Sperry and the Dixon.

Wow, talk about a trip down memory lane! Thanks, Peter.

Thanks Peter! I have learned that your recommendation is?always reliable on books. Will get those books.

The covers of both Wahoo and Clear The Bridge carry words of praise from Edward L. Beach, author of Run Silent, Run Deep. If anyone has not read that book, It is a novel that gives an excellent overview of the USN WW2 submarine campaign in the Pacific: the early training, the feedback from war patrols, the torpedo problems, simulator training for officers, etc. I find that, having read that, the stories of the real men who pioneered and perfected the tactics are even more impressive.

Another sub book, from the German side .. Iron Coffins .. is a compelling read.

Just read Clear The Bridge, and was waiting for the f-up that sank them. News flash; there wasn't, it was something else, not their fault.

A great book, with a detailed look at five war patrols. Recommended reading for any WWII or submarine buff.

Matt

St Paul

Interesting that Edward L. Beach's Run Silent, Run Deep has been mentioned. Beach based some of the novel on historical accounts of Wahoo and Tang. The killing of Japanese survivors in lifeboats in the novel echoed actions that the CO of Wahoo, LCDR Dudley "Mush" Morton, took against similar survivors while he was commanding Wahoo. The story continues in Beach's two sequels to Run Silent, Run Deep: Dust On the Sea and Cold Is the Sea.

Decades ago, I stumbled onto Clay Blair's unbelievably complete history of the US Pacific submarine war, "Silent Victory".

An enlisted man who served in submarines, he described his book as the story of the commanders and officers.

I've read it at least three times or more over the years, each time more in awe of the men who served in subs in the Pacific.