For over half a century, aviation has been taken for granted by the public. From the end of World War II, civil aviation has offered fast, convenient service to almost anywhere on Earth (or, at least, near enough to make it easy to get the rest of the way by alternative means of transport). Accidents, while tragic and often spectacular, are relatively rare. Flying is (statistically speaking) the safest means of mass transport out there.

It wasn’t always that way.

We tend to forget that one of the primary attributes of those who paved the way for future fliers wasn’t skill, or knowledge, or enthusiasm (although they had all those in plenty). It was sheer, raw courage. They put their lives on the line every time they took off in their flimsy, frequently unreliable aircraft. With tragic regularity, some of them fell off that line and became statistics.

The Atlantic Ocean was probably the most difficult obstacle to overcome in the first quarter-century of flight. It claimed the lives of many fliers, and continued to do so even in the safer years that followed. Over the next three instalments of Weekend Wings I’d like to pay tribute to some of the gutsy, daring pioneers who first tamed the Atlantic.

In 1913 Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the London Daily Mail newspaper (amongst other media holdings), announced a prize of £10,000 (about $50,000 at then-current exchange rates, and worth about twenty times that today). It would be awarded to the first pilot(s) to cross the Atlantic in either direction between the North American continent and any point in the British Isles (including, at the time, all of Ireland). The flight had to take no longer than 72 consecutive hours, and the pilot had to finish in the same aircraft with which he started. Intermediate stops could only take place on water, and the pilot would have to take off again from approximately the same place he landed.

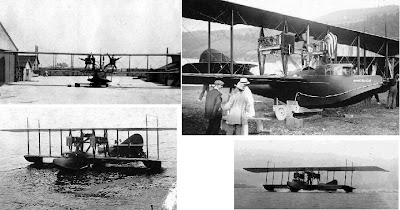

Glenn Curtiss, the first pilot to take off and land on water, was eager to take up the challenge. He posted the $500 entry fee and designed a flying boat for the crossing, named the America. (Click this and all other pictures for a larger view.)

By August 1914 it was ready, and the flight was scheduled for the 5th . . . only to have World War I break out on August 3rd. The dream of a Trans-Atlantic flight disappeared for the duration.

Towards the end of the war the US Navy contracted with the Curtiss Aeroplane And Motor Company to develop a new flying boat, very large for its day. It was designed for anti-submarine patrol, and the Navy specified that if possible it was to be able to fly across the Atlantic. This was desirable due to the menace of German submarines, which would make transporting it by ship too risky. Four aircraft were ordered in the first batch.

The prototype Curtiss NC-1 was powered by three 400hp Liberty L-12 engines in a tractor configuration (i.e. the propellers were mounted ahead of the engines, pulling the aircraft forward). It was equipped with a wireless transmitter and receiver and crew sleeping quarters. It first flew on October 4th, 1918.

In November 1918 it flew with 51 people on board, a world record. The three-engine configuration proved to be underpowered, so a fourth engine was added to subsequent aircraft. It was installed in an elongated central nacelle containing two engines. One pointed forward in tractor configuration, and another was mounted behind it in pusher configuration (i.e. the engine was reversed, pointing to the rear of the aircraft, with the propeller pushing air towards the tail). The pusher propeller had four blades, while the three tractor propellers had only two. This unique configuration is shown in the close-up photograph of the NC-4’s engines below. Note the radiators mounted above the engines, behind the propellers.

The NC-2 was damaged during testing, and was cannibalized for spare parts. The NC-1 (upgraded to production standard), NC-3 and NC-4 went into service with the US Navy in early 1919. From their initials, they became affectionately known as the Nancy’s.

Following the end of the war, British and other fliers were planning an assault on the North Atlantic, with the revived Daily Mail prize as a tempting reward. However, the rules had changed. No “ocean stoppages” would be permitted, and no aircraft of “enemy origin” were eligible. This barred the US Navy’s giant flying boats and the large German bomber aircraft, both developed towards the end of the war, from competing.

Undaunted, the US Navy set up a Trans-Atlantic Flight Planning Committee to consider an attempt using its new NC flying boats. Commander G. C. Westerfelt submitted a 5,000-word proposal to the Committee, recommending the use of what he called “stake boats” at regular intervals along the course. They would serve as navigational route markers, and also rescue any fliers that had to come down in the water. His proposal was accepted by the Committee, which forwarded it to the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels. It was enthusiastically supported by the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and quickly approved.

The plan was initially classified “Secret”, but due to an administrative oversight, orders assigning Commander John H. Towers to command NC Seaplane Division One, which would undertake the mission, were left unclassified and released to the press. A firestorm of publicity followed. (Towers would go on to become second-in-command of the Pacific Fleet during World War II, and command it after the war. Another famous admiral from World War II was also involved in the transatlantic flight: Lieutenant-Commander Mark A. Mitscher was one of the pilots aboard NC-1.)

The US Navy made an enormous commitment of time, money and ships to the project – almost 60 vessels, from destroyers to battleships, would be involved as “stake boats”, and others would serve as “mother ships” for the flying boats. Naval Air Station Rockaway in New Jersey was selected as the start point for the trip. The photograph below shows two of the Nancy’s, NC-3 and NC-4, at NAS Rockaway.

The attempt was almost derailed by a disastrous hangar fire on May 5th, 1919, which destroyed the tail of NC-4 and one wing of NC-1. However, Commander Towers recalled that some parts had been cannibalized from the decommissioned NC-2. Frantic telephone calls ascertained that NC-2’s tail and wings were still available. They were rushed to NAS Rockaway and transplanted onto the damaged Nancy’s, just in time for the flight.

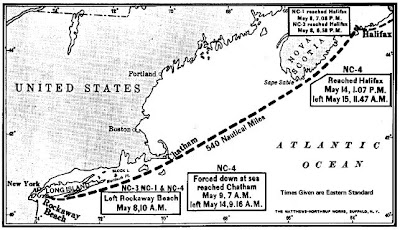

On May 8th, 1919, the three Nancy’s set off from Rockaway for Halifax, Nova Scotia. NC-1 and NC-3 made it safely, but NC-4, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Albert C. Read, was forced down at sea due to engine failure. She had to undergo repairs at Chatham Naval Air Station on Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

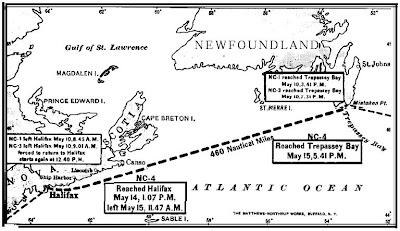

The following day NC-1 and NC-3 flew to Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, where NC-4 joined them on May 15th. She was almost too late: as she flew in over the bay, Read was horrified to see the other two Nancy’s taxiing for take-off! Fortunately for NC-4’s crew neither of the other two aircraft was able to get airborne that day, probably due to a fuel overload. NC-4 joined her squadron-mates, and the crews prepared their aircraft for the long leg across the Atlantic to the Azores.

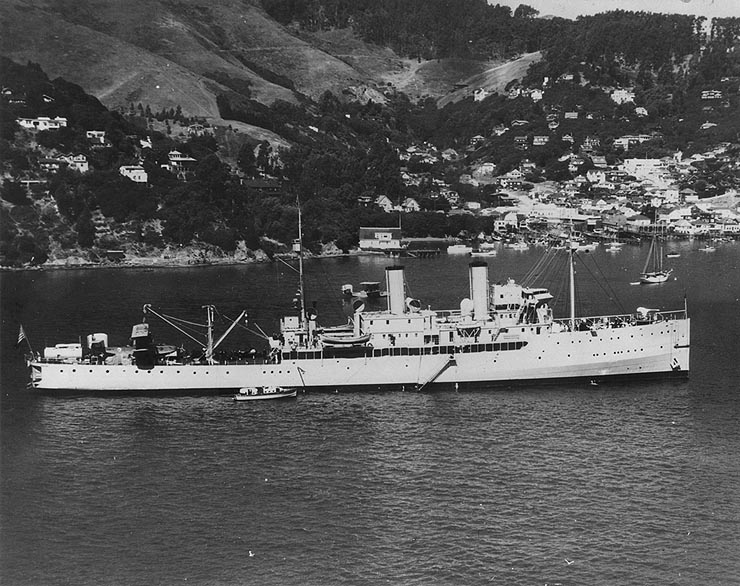

Waiting for them in Trepassey Bay was the USS Aroostook, which had laid moorings for the flying boats. She would serve as their tender or “mother ship” while they waited to tackle the Atlantic. The first picture below shows her in an unknown harbor. In the second, NC-3 is taxiing past her in Trepassey Bay. NC-1 is moored in the background. NC-4 had not yet arrived.

All the Nancy’s had experienced problems of one sort or another. NC-4 had been forced down at sea on two occasions due to engine problems, and she had a new engine installed at Trepassey Bay. There was no time to test it thoroughly, as the aircraft had to take advantage of the first favorable weather forecast. They waited at the moorings laid for them.

Also in Newfoundland was a US Navy patrol airship, the C-5, which was intended as a backup craft in case the Nancy’s couldn’t make the crossing. I couldn’t locate a photograph of C-5, but the one below shows her sister airship, the C-7.

Unfortunately, C-5 broke loose from her moorings on May 15th during a gale (fortunately while no-one was aboard). She was blown out to sea and lost. Everything was now up to the flying boats.

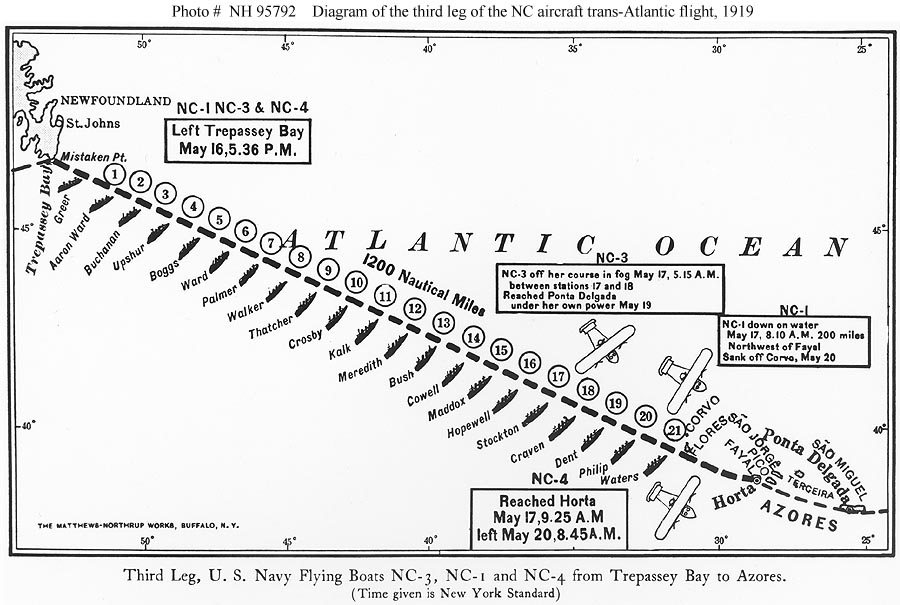

On May 16th the Nancy’s took off for the Azores. It was a difficult take-off, the heavily laden aircraft having to run cross-wind, and Commander Towers offloaded his radio transmitter in an attempt to save weight. All three finally made it into the air by late afternoon, and set off into the night.

The three photographs below show, from top to bottom, NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4 taking off from Trepassey Bay for the transatlantic flight.

Try to imagine the enormous difficulties facing the crews of the Nancy’s. They were flying in open-cockpit aircraft, exposed to the freezing cold of the North Atlantic (they flew over icebergs for the first part of the journey). Each waiting warship was to transmit a message as soon as the aircraft flew over them, whereupon the next ship would commence firing star-shells at 5-minute intervals to guide the aircraft to them: but what if the aircraft became widely separated? The first aircraft would precipitate the signal, but then the ship sending it would stop firing star-shells. The following aircraft would thus be deprived of navigational references. Also, the presence of the ships was no guarantee of accuracy. As Commander Towers said later:

“Those who think that having destroyers 50 miles apart made navigation as easy as ‘walking down Broadway’ should have been with us that evening. It was not until darkness came on and they began to fire star shells at five-minute intervals that I could think of anything but finding the next destroyer. They could not be expected to be exactly on position, and if we didn’t find them just where we expected them, there was always the question, are they wrong or are we?”

The destroyers had been ordered to shoot to the North-West, at an angle of 75°, with their fuses set to detonate at 4,000 feet. The aircraft had been instructed to fly to the South of the ships, supposedly eliminating the risk of being hit by the star-shells. Unfortunately, that wasn’t always the case. As Commander Towers later reported:

“I had set a course which was taking us by the destroyers, just south of them, like clockwork, when finally as we approached one, it was apparent we would pass to north of it. I thought it was out of position and was reluctant to change my heading. Besides, I could see through the thin clouds and thought they could see us, too, so I kept right on. Having timed their shooting, I knew they were due to fire just about as we were in line. Either the destroyer didn’t see us or they didn’t believe in deviating one iota from their instructions for, right on the second, I saw the flash from the gun. The star shell exploded just under us. I glanced back and in the moonlight both Richardson and McCulloch looked as though they would like to take the navigation out of my hands.”

The Nancy’s carried special navigation instruments designed by US Navy Lieutenant R. E. Byrd, later to become a renowned polar explorer and Rear-Admiral. These instruments were of great importance, helping the aircraft stay on course at night, in cross-winds, and measure drift in the absence of any fixed landmarks. Improved versions would later accompany Byrd on his famous flight across the North Pole.

Thick fog added to the difficulties of navigation. After station ship 13, USS Bush, Towers in NC-3 did not see any more of the destroyers. He navigated by dead reckoning until he felt sure he was near the Azores. Afraid he might hit a mountain, he landed NC-3 in the Atlantic: but the huge swells damaged the aircraft so badly it could not take off again. The NC-1 did the same, suffering the loss of the lower section of her tail. Destroyers began searching for them, but NC-3 was South of the predicted course and NC-1 was North of it. Finding them would be neither quick nor easy.

Read in NC-4 had a much easier time of it. He chose to fly high, at about 3,000 feet, between layers of cloud. At that height fog wasn’t a factor. He finally sighted the Azores at about 9.30 a.m. on May 17th. He was supposed to fly to Punta Delgado, but due to the poor weather decided to cut his journey short. He landed initially in the Bay of Praia, but after getting his bearings took off again and landed at the nearby harbor of Horta, where the cruiser USS Columbia was waiting.

Meanwhile, the rescue drama at sea was playing out. NC-1 sent an emergency message, and for five hours her crew ran the engines to keep her head to the mountainous waves, bailing out water and getting very seasick. Finally the Greek merchant ship Ionia appeared. Attempts to take NC-1 in tow failed due to the heavy seas, and the crew was evacuated. NC-1 sank, and her crew was taken to the Columbia in Horta.

Commander Towers in NC-3 accomplished a truly amazing feat of seamanship. He couldn’t radio for help, having landed his transmitter before leaving Trepassey Bay. He and his crew sailed NC-3 backwards for 205 miles. He brought NC-3 to anchor in Punta Delgado on May 19th. The aircraft was too badly damaged to continue, which was a bitter disappointment to Towers, but he and his crew’s courage and determination in the face of overwhelming odds were justly acclaimed.

Read brought NC-4 to Punta Delgado on May 20th. The photograph below shows her anchored in the bay.

Meanwhile, an Australian pilot, Harry Hawker, and his navigator, Kenneth Grieve, took off from Newfoundland on May 18th to attempt the crossing. They disappeared in mid-Atlantic, and for a time were presumed to have drowned. Fortunately they were picked up by a passing ship, but she didn’t have a radio transmitter, so their whereabouts weren’t known for some days. Their presumed loss shook Britain and saddened their American counterparts in the Azores.

Commander Towers might have expected to take over NC-4 from Lieutenant-Commander Read to complete the journey. However, Secretary Daniels was adamant that since Read had been successful so far, he was to complete the journey. Towers was ordered to travel to England by destroyer. He must have been a very frustrated man!

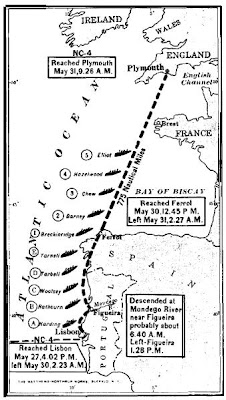

Read took off from Punta Delgado early on the morning of May 27th, reaching Lisbon that evening. NC-4 thus became the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic, albeit with a mid-ocean stop-over. The map below, showing the warships stationed en route, has a small segment missing in the middle due to a defective original, but is otherwise accurate.

The photograph below shows NC-4 taxiing into Lisbon harbor.

On May 30th NC-4 left Lisbon for Plymouth, England, to complete her epic journey. After an overnight stop at Ferrol, Spain, she arrived on 31st May.

USS Aroostook was waiting, having lifted the moorings she’d laid in Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, then crossed the Atlantic to rendezvous with the flyers. Aroostook set about dismantling the NC-4 to ferry her back to America, while Read and his crew were lionized by the British press and aviation enthusiasts for their accomplishment. They attended civic receptions in Plymouth and London. The celebrations were enhanced by the safe arrival of the rescued Hawker and Grieve, who met NC-4’s crew and exchanged congratulations.

The photograph below shows the six-man crew of NC-4, the first people to cross the Atlantic Ocean by air. From left to right: Lt. E. F. Stone, USCG, pilot; Chief Machinist’s Mate (Air) E. T. Rhoads, USN, Engineer; Lt. W. K. Hinton, USNRF, Pilot; Ens. H. C. Rodd, USNRF, Radio Operator; Lt. J. L. Breese, USNRF, Reserve Engineer; and LCdr. A. C. Read, USN, Commanding Officer and Navigator.

Upon their return to the USA the transatlantic flyers were greeted as heroes. Read made a recruiting tour of 39 cities, and NC-4 was restored to flying condition and sent around the country for the same purpose. She’s shown here after reassembly. (You can get some idea of how big she is from the size of her pilots and crew.)

Six more NC series flying boats were ordered, NC-5 through NC-10. NC-4 made her final operational flight in 1922, and was put into storage. Many years later she was fully restored, and is now on display in the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, FL, where her huge bulk dominates one wing of the display area.

She’s well worth a visit (as is the whole Museum, one of my favorites. If you haven’t been there, it’s something you really should put on your “must-see” list.)

Somewhat belatedly, in 1929, the US Navy issued the NC-4 Medal to honor the achievement of Read’s successful crew. It was awarded to only seven recipients: Read’s crew and Commander Towers, who qualified for it as the overall Commanding Officer of the mission. It’s one of the rarest US military medals. The names of all of NC-4’s crew are inscribed on the medal, but Chief Rhoads’ surname is wrongly spelled. He must have been more than a little irritated, as the mistake could never be corrected!

NC-4’s flight was to be overshadowed within two weeks of its completion by another aircraft and crew. We’ll talk about them in the next Weekend Wings.

Peter

Much enjoyed the story on the NC-4 flight. As a collector of US medals a memory I will always treasure is holding Chief Rhodes gold congressional medal. I tried to find a picture to post but couldn’t. It’s similar to the one in your photo except it’s a table medal. The example I held is about three inches in diameter and 1/4 inch thick of 14k gold. The gold value would be incredible but as a history buff it is irrelevant. Thanks again.

Greg Gritsch (on API)

Thank you very much for putting this fantastic story out.