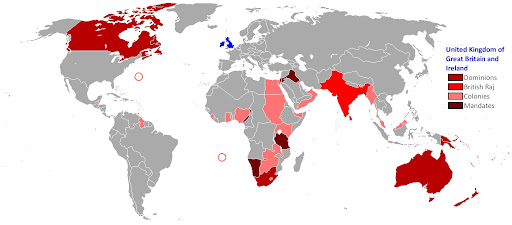

After the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended World War I, the British Empire was at its largest. It covered almost 25% of the world’s land mass, and was spread around the globe.

Sea communications between Britain and her various territories was well established, and during the War aviation had advanced to the point where air links had become a practical possibility. The 1920’s and 1930’s would see these links established, forming the longest-distance air transport network in the world prior to the post-World War II boom in commercial aviation.

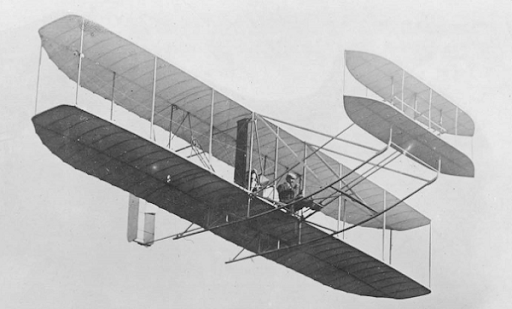

The story of the Empire’s air networks is also, in large measure, the story of the oldest true aviation firm in the world: Short Brothers (usually referred to as ‘Shorts’, as we’ll do in the rest of this article). The company was established in 1908 to manufacture the Wright Model A biplane under license for the British market.

Shorts contracted to build an initial order of six Model A’s, all purchased by members of the Aero Club (which became the Royal Aero Club in 1909). This made the firm the first airplane manufacturing company in the world, as the Wright brothers had not set up their own corporate entity at that stage. (They established the Wright Company in 1909.)

Shorts immediately began designing aircraft themselves. We can’t spend too much time on their general aircraft, which would make a fascinating study in early designs in their own right. Here are a few pictures of some of the early highlights.

This won the Daily Mail prize for the first British aircraft

to complete a circular course of one mile.

aircraft to be produced by the company over the next four decades.

During World War I the Short Type 184 seaplane (shown below) was widely used by the Royal Navy and allied naval forces, a total of 936 being built by ten companies.

It was a torpedo- and bomb-carrying reconnaissance aircraft. Type 184’s based aboard HMS Ben-my-Chree, a seaplane carrier (shown below), serving in the Dardanelles during the Gallipoli Campaign, made the first torpedo attacks by aircraft against ships in August 1915.

One of these attacks is probably unique in aviation history. On August 17th, 1915, Flight-Lieutenant G. B. Dacre was forced to land on the sea following engine trouble with his Type 184. A nearby Turkish tugboat approached, presumably intending to capture the plane and its pilot. Determined to avoid so ignominious a fate, Fl-Lt. Dacre taxied his aircraft towards the tug, aimed carefully, and fired his torpedo from the surface, rather than air-dropping it in the normal way. His weapon, launched at point-blank range, could hardly miss, and sank the tug. He was then able to make hurried adjustments to his engine and take off again, returning safely to HMS Ben-my-Chree. I’ve no doubt that the tug’s survivors, floundering in the water, hurled some horrible language after him as he cheekily flew off into the distance!

At this point, it’s worth noting the difference between seaplanes and flying-boats. A seaplane is an aircraft which is supported above the water by floats mounted beneath the fuselage and/or wings. A flying-boat’s fuselage is boat-shaped and floats in the water, using additional floats or sponsons to keep the wings and engines clear of the surface. Seaplanes are typically smaller aircraft, whereas flying-boats (such as the massive Boeing 314 Pacific Clipper, which we covered in Weekend Wings #23) can be much larger.

Flying-boats were developed into stable, reliable aircraft during World War I. The Royal Navy ordered some Curtiss flying-boats from the USA, and these were further improved by the designs of Wing Commander J. C. Porte, who developed the Felixstowe series of flying-boats based on the earlier Curtiss designs. The last of these, the Felixstowe F.5, served as the Royal Air Force’s standard flying-boat until the mid-1920’s. It was sufficiently advanced that the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company (on whose pre-war designs, remember, the Felixstowe series had been based) manufactured it in the USA (using US-built Liberty engines rather than the Rolls-Royce Eagle engines used in British aircraft) as the Curtiss F5L (shown below) for service with the US Navy. Civilian models of the Curtiss F5L were known as the Aeromarine 75.

Short Brothers had been amongst the factories manufacturing the Felixstowe F.3 and F.5 flying-boats during World War I. This experience, plus their extensive work with seaplanes, convinced them that such aircraft would be of vital importance to the expansion of commercial air travel in the near future. Water-based aircraft seemed much more promising than land-based planes, for three fundamental reasons.

- There were very few large airports available around the world. To establish them would be time-consuming and very expensive, considering the many thousands of miles over which materials and trained personnel would have to be transported. In addition, the concept of an ‘all-weather’ airport had not even been considered up to this point. All airports used grass or gravel runways, which became almost unusable after heavy rain. There were none of the aids to navigation such as radar, radio beacons, etc. to which we’re accustomed today, making it difficult to locate such airports in bad weather or during the hours of darkness.

- There were many large bodies of water near major cities that could be used to land seaplanes or flying-boats. No runways or other infrastructure would be needed; only a line of buoys to mark the preferred ‘runway’. Shore facilities could be restricted to shelters for passengers, luggage and cargo, plus a jetty to make it easy and convenient to board small craft for the trip to and from the aircraft. In addition, such bodies of water could be identified from the air relatively easily, given only a small amount of light (e.g. moonlight). To find them, an aircraft could follow the coastline, or fly over land until it spotted the lake on which it was to land; then it was simply a matter of flying low over the water’s edge until it came to a signal light or fire marking its point of arrival. Landing instructions such as wind direction, etc. could be passed by radio or signal lamp.

- The relatively poor reliability of early aircraft engines was a serious obstacle to the development of commercial aviation. If an engine or engines failed on a land-based plane, it had to find smooth, level terrain to land (which wasn’t often available), or crash. A seaplane or flying-boat, on the other hand, could touch down on any relatively calm stretch of water, and float there until repairs could be made or a vessel could be sent to tow the aircraft to safety. It could also be routed from point to point to make sure that as much of the flight path as possible was over or near water, making emergency landings safer. The only real dangers were storms, making the water too rough for a safe landing, or heavy maritime traffic, posing a risk of collision. Both risks could be minimized by careful forecasting and planning.

These factors outweighed the otherwise very real disadvantages of flying-boats as long-range transports, which included:

- A flying-boat’s hull had to contain enough volume to permit the aircraft to float. This meant it had to be significantly larger than the hull of a land-based aircraft of similar performance, which could support itself on wheels. Also, the hull had to be strong enough to take the pounding of waves and small items of debris during take-off and landing, requiring strong fuselage and wing members and structural reinforcement. Both of these factors – size and strength – meant that a flying-boat would be larger and heavier than a land-based plane capable of carrying the same number of passengers, or the same weight of cargo. In turn, that increased size and weight translated into a need for more powerful engines, which consumed more fuel, which required more fuel to be carried for a given range, which in turn added more weight and bulk to the plane.

- The added size, weight and complexity of flying-boats made them relatively expensive to build, buy and operate. It wasn’t unusual for a flying-boat to cost three times as much as a landplane capable of carrying as many passengers or as much cargo. In addition, their operation was much more complex, as their crews had to be able to navigate them on the water (obeying maritime rules of the road) as well as fly them. This demanded extreme professionalism from pilots and their assistants. The corps of flying-boat crews that arose in Britain and the USA during the 1930’s was, indeed, remarkable in their professionalism: but they took a long time to gain the necessary experience, and were expensive to retain. Few would survive the Second World War.

- A flying-boat’s hull had to move easily through the water, then rise above it to break free of its grip when taking off, then move smoothly through the air during flight, and finally transition from high-speed flight to low-speed maneuvering on the water once more. The only shape that could achieve all those things proved to be a lot less aerodynamic than a simple cylinder- or box-shaped fuselage as found on land-based aircraft. This increased wind resistance meant that flying-boats would not be able to keep up with improvements in speed, range and efficiency of their conventional counterparts. In the early decades of flight, when nothing could fly very fast or very far, this wasn’t a major drawback: but as engines became more powerful and more reliable, land-based aircraft inevitably came to surpass flying-boats in almost every category of performance. This would ultimately prove the latter’s downfall.

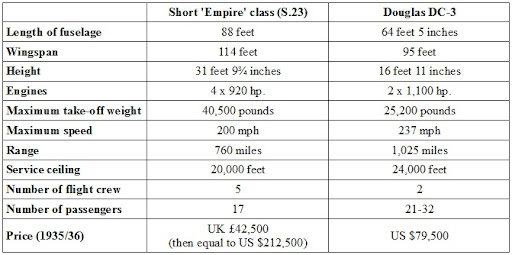

To summarize these disadvantages, let’s compare the Short Empire flying boat of the mid-1930’s with the premier US land-based airliner of the same period, the Douglas DC-3. Both are shown below.

As you can see, the DC-3 could carry more passengers, further, faster and higher than the S.23, with half the number of engines and crew, for about one-third of the capital cost. That’s the sort of penalty incurred by a flying-boat’s larger, heavier and much more complex design (although its more luxurious and roomy interior played a part as well, as did the space required for its mail cargo).

That said, we’ve gotten a bit ahead of ourselves: so let’s return to the commercial aviation situation at the end of World War I. Numerous airlines started up post-war, most using converted military aircraft, and airmail routes were soon established connecting Britain and Europe. The British colonial administration soon began to think of ways of extending an airmail service to connect all of the far-flung territories it controlled; but no aircraft had sufficient range (or reliability) in those days to provide such a service. Nevertheless, the goal was there, and it inspired both officialdom and aircraft manufacturers to look to the future.

Four small airlines in particular interest us. The first was British Marine Air Navigation Company Ltd., flying three Supermarine Sea Eagle flying-boats (which entered service in 1923) between England, the Channel Islands and France.

The Daimler Airway flew between London and Paris, and later to Germany as well, operating (initially) six de Havilland DH.34 single-engined cabin biplane airliners.

Handley Page Transport Ltd. also flew the London-Paris route, initially using converted Handley Page O/400 bombers (the largest British aircraft of World War I) modified to carry passengers.

It later adopted the Handley Page Type W8 airliner.

The Instone Air Line operated from Cardiff in Wales to London, Paris and Cologne in Germany, flying a number of different types of aircraft, among them a Vimy Commercial (an adaptation of the Vickers Vimy bomber of World War I, replacing the narrow bomber fuselage with a much fatter one providing passenger and cargo space) and several de Havilland DH.34’s.

It became clear both to these airlines, and to the British Government, that competing with one another over the relatively low volume of air passenger traffic between London and Paris was going to get them nowhere. In addition, the Government urgently wanted to extend air services further than the continent of Europe, to the Empire in general. Accordingly, Imperial Airways was formed in March 1924 by merging the four airlines mentioned above. The British Government provided a one-million-pound subsidy over ten years as an incentive.

Imperial Airways continued its air connections to Europe, but did not immediately operate further afield, as suitable aircraft weren’t available. It issued specifications to various aircraft manufacturers for better equipment, and as soon as this was developed it began to expand its services. In 1927 it initiated services from Cairo in Egypt to Basra in Iraq, but it was only in 1929 that the first through service from London to Karachi (then in India, today part of Pakistan), was begun.

At the time Imperial Airways was formed, Shorts was developing what would become the Short Singapore military flying-boat for the Royal Air Force. The Singapore was a graceful and very successful aircraft, going through three Marks in production. It was noteworthy for having four engines mounted in two pairs, driving both a tractor and a pusher propeller with each pair. The Singapore Mark III was still in service at the beginning of World War II.

Shorts adapted its Singapore design to meet Imperial Airways’ specifications for a mail- and passenger-carrying flying-boat, and in 1928 produced the three-engined Calcutta. It could carry 15 passengers at a cruising speed just below 100 mph, over distances of five to six hundred miles. It went into service in 1929 on the Mediterranean routes of Imperial Airways, which bought seven of them. Passengers would fly from London to Paris, then take a train to Marseilles on the Mediterranean coast, where they boarded a Calcutta. This flew them via Italy and Greece to Alexandria in Egypt. Flying-boat service continued via Iraq and the Persian Gulf to Karachi, in what is today Pakistan, or passengers could transfer at Alexandria to land-based aircraft to fly down the continent of Africa.

For those interested in learning more about the Calcutta, a complete contemporary review is available here (link is to a 26-page file in Adobe Acrobat .PDF format).

Imperial Airways needed land-based aircraft for the London to Paris leg, and to extend its colonial routes from water termini such as Alexandria. It bought a number of aircraft for the purpose. A Handley Page W9 and four W10’s soon arrived: they were similar to the W8 shown above, the W9 having three more powerful engines and the W10 two engines of even greater power. However, new designs better suited to Imperial Airways’ needs were on the drawing-boards.

The first to enter service with the airline was the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy. This tri-motor biplane could carry 20 passengers at a cruising speed of only about 90 mph, with a range of 400 miles.

The Argosy’s cabin was more spacious than earlier designs, to provide greater comfort to passengers who might spend long hours, even days, aboard her over Imperial Airways’ long colonial routes.

Another new acquisition was the de Havilland DH.66 Hercules, a three-engined biplane introduced initially to carry air mail between Cairo, Egypt and Baghdad, Iraq. Imperial Airways configured it to carry seven passengers in addition to a large postal cargo.

The Hercules was also used on some direct Imperial Airways flights between England and India, routed via land bases in Europe and the Middle East, and by West Australian Airways (in a 16-passenger configuration, with the air mail cargo space correspondingly reduced) to provide a service from Perth to Adelaide.

To provide this service, Imperial Airways began a detailed survey of air routes immediately after its formation. It would fly over some of the most desolate, hostile and dangerous environments in the world. Outposts were built across the Arabian desert and down the River Nile in Africa, including weather services, radio stations and emergency landing grounds. A unique navigation aid was provided: a giant furrow, several hundred miles long, was plowed into the desert between Palestine and Iraq, to show aircraft which direction to fly!

The first service from Cairo to Karachi via Baghdad was initiated by Calcutta flying-boats in 1927. In March 1929 a direct route from London to Karachi was launched, using landplanes, but this did not replace the standard flying-boat service; it was designed for urgent airmail, with passenger transport a secondary consideration. The new service cut the three-week transit time by sea to just one week.

The Argosy and Hercules were useful smaller aircraft, but simply couldn’t carry enough passengers and cargo to provide an adequate feeder service from flying-boat ports of call to stations further down the Imperial Airways network. To do this, a new and much larger design was needed. It was provided by the four-engined Handley Page HP.42 and HP.45, which were built to a 1928 Imperial Airways specification.

Despite their different numerical designations, the HP.42 and HP.45 were the same basic aircraft. The HP.42 was configured for the long-range air routes in the Middle and Far East, carrying fewer passengers (18-24) and more fuel, while the HP.45 carried less fuel and had reduced baggage capacity, but could seat up to 38 passengers for the shorter, more popular European routes. Imperial Airways bought four of each model.

Here’s a short video clip of the Handley Page HP.42.

Despite the advent of these land-based aircraft, the long-range routes of Imperial Airways continued to rely on flying-boats, as much because these required few or no base facilities as for any other reason. To survey surface sites and then erect landing-grounds, radio stations, fuel depots and other air transport essentials was extremely expensive, particularly when no supporting infrastructure (e.g. electric power, hospitals, roads, etc.) existed! A flying-boat’s needs, on the other hand, could be met by stationing a depot ship or boat on any convenient body of water, and sending another vessel at intervals to resupply the floating base, which was thus rendered self-sufficient and independent of the wilderness or primitive conditions that might surround it.

In 1929 Italian airports and harbors were closed to Imperial Airways due to a diplomatic dispute. This produced problems for the relatively short-ranged Calcutta flying-boats, which had to be diverted via Malta around the bottom of Italy. To help solve the problem, Imperial Airways asked Shorts to design a larger, longer-ranged flying-boat. Their response was the Kent, essentially an enlarged Calcutta with the same 15-passenger capacity but more room for mail and greater fuel capacity. Powered by four engines, it had sufficient range to bypass the bottleneck of Italian territory.

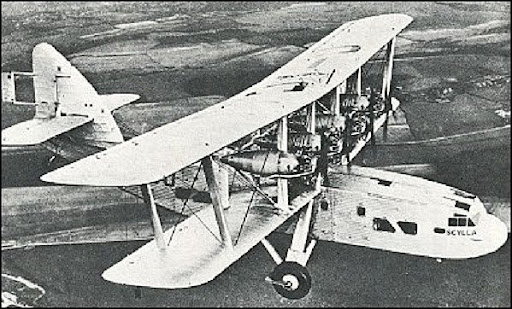

Three were bought by Imperial Airways, and two more were ordered in a landplane version, known as the Scylla, which used the same wings and engines as the Kent atop a new and smaller fuselage with wheels. It could carry up to 39 passengers (comparable to the Handley Page HP.45).

The very small number of these aircraft ordered illustrates one of the perennial problems of the British aviation industry. Imperial Airways was the only airline requiring such large and (for the time) sophisticated airplanes. Others, focusing on local or cross-Channel routes, could use smaller, cheaper and simpler aircraft. As a result, there was no standardized mass production model for civil airliners, such as developed in the USA, where there were many more airlines flying long internal routes, who needed far more than two or three aircraft apiece. This, amongst other factors, would contribute to Britain’s eventual loss of control over the civil aircraft market to the USA after World War II.

Such small orders also stifled innovation. Where US manufacturers such as Boeing and Douglas were ‘pushing the envelope’ to produce larger, faster and more capable aircraft, driven by the demands of an expanding internal airline network, there was no such pressure on British manufacturers. During the 1930’s new land-based airliners would be taken into Imperial Airways service, but with few other airlines to order them, and consequently small production runs, the new aircraft would not greatly exceed the performance of those already in service. Examples include the Armstrong Whitworth AW.15 Atalanta of 1932.

It was capable of carrying up to 17 passengers, although in Imperial Airways service it was limited to 9 or 11, depending on its route. Only 8 were ordered by Imperial. Armstrong Whitworth also produced the AW.27 Ensign of 1938, carrying up to 40 passengers (depending on configuration), which flew with a distinctive nose-down attitude.

Again, Imperial Airways was the only customer, buying 14 of them.

Shortly before World War II, Imperial bought 7 of what may have been the most visually attractive British airliner of the period, the de Havilland DH.91 Albatross.

Very fast for its day, the aircraft was constructed out of plywood, a forerunner of the world-famous de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito fighter-bomber of World War II. However, only seven were built, five as passenger aircraft and the two prototypes as mail carriers. None survived the war.

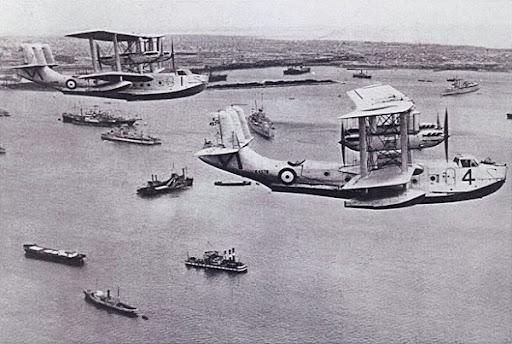

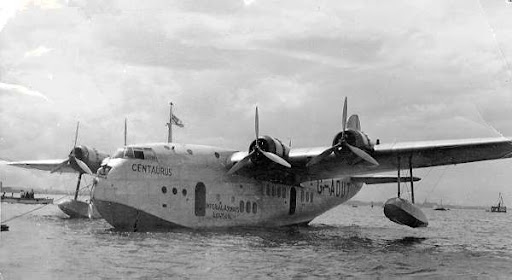

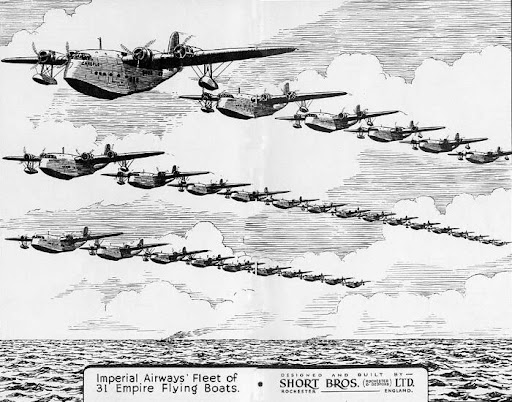

However, none of these aircraft would suffice for the long stretches of the Empire’s air routes where there were few or no support stations. Flying-boats remained the vehicle of choice for such routes, and Imperial turned to Shorts once more for a solution to their ever-expanding network requirements. Shorts responded with an iconic aircraft, one that above all others tends to symbolize the so-called Golden Age of European air transport in the 1930’s: the Empire class of flying-boats. They could carry 5 crew, 17 passengers and up to 4,480 pounds of cargo.

A total of 42 of these ‘C’ class flying-boats (so called because their names all began with the letter ‘C’) would be ordered by Imperial Airways and its successor, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), in three different production classes: S.23, S.30 and S.33. They would provide the backbone of the Empire Air Mail Service before World War II, and provide yeoman service during the war to keep communication lines open.

They landed and took off from the sea, rivers, lakes, lagoons – any suitable body of water. Apart from handling the trans-Mediterranean traffic of Imperial Airways, they flew down the Nile and along the East African coast to reach South Africa; crossed the Arabian Desert, then flew down the Persian Gulf and across the Indian Ocean to Australia and New Zealand; and, in larger models (of which more later) would also handle trans-Atlantic traffic to Canada, the USA and Bermuda.

Several Empire flying-boats were purchased by the Australian airline Qantas, which partnered with Imperial Airways to handle the Antipodean legs of the trans-Empire air route.

Here’s a series of video clips of the building and introduction of the Empire flying-boats.

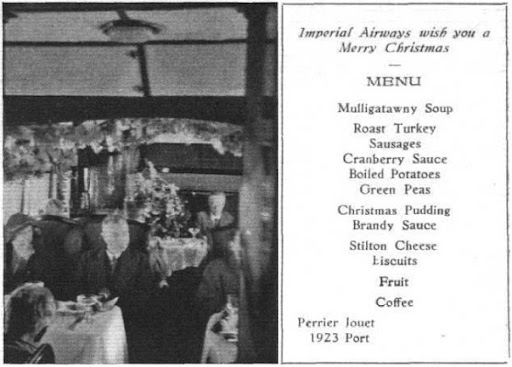

The Empire flying-boats were luxuriously equipped, to make their passengers as comfortable as possible during the long hours and days of their journey. This Qantas advertisement shows passengers standing in the lounge, looking out of the window, while children (and their dog) play on the floor. Looks a bit different to modern airliners jammed with passengers like sardines in a can, doesn’t it?

The menus served on board were also rather superior to today’s peanuts and pretzels. As Flight magazine reported on January 25th, 1934:

Imperial Airways always look after their passengers better, perhaps, than any other transport company in the world, and an amusing and effective example of this care is given by the Christmas lunch so carefully arranged for the passengers in Scipio, the four-engined Short [Kent-class] flying boat which was to leave Brindisi on the morning of December 25, 1933, for Athens.

. . .

The staff of the Scipio, in command of Capt. F. J. Bailey, had decorated the cabin very carefully with holly, mistletoe and paper streamers, and a Christmas tree had been rigged up. This was suitably decorated and hung with gifts for each of the 14 passengers, in the shape of Imperial Airways diaries with the passenger’s names.

The tree was a fully illuminated one, with coloured lamps lit from the ship’s electrical system. The lunch, which had been supplied by Fortnum & Mason, Ltd., was a great success. The turkey was served cold, but the soup, sausages, potatoes and pudding were all hot. Just how this was done had better remain a secret of Imperial Airways, as a cursory glance at the facilities the steward has in his pantry does not appear to offer any solution. The fact remains, however, that when they do give their passengers anything hot it is really hot.

Shorts weren’t slow to take advantage of the name recognition conferred on them by the worldwide presence of the Empire class flying-boats. Here’s one of their advertisements from the 1930’s.

Readers will recall that the first flying-boats Shorts built for Imperial Airways, the Calcutta class, were derived from their Singapore flying-boat built for the Royal Air Force. It’s perhaps fitting, therefore, that the Empire flying-boats served as the pattern for the enormously successful Sunderland military flying-boat. The prototype of the Sunderland first flew in 1937, and well over 700 were built in various Marks during World War II. A number were converted for civilian use to replace Empire flying-boats that had been lost due to weather, accidents or enemy action. Those converted during the war were known as the Hythe model, and 29 were operated by BOAC by the end of the war. Post-war conversions were known as the Sandringham model.

The Sunderland was probably the most effective military aircraft of its type in history. Some would argue – and I would agree – that the US Consolidated PBY Catalina was at least as successful, operationally speaking: but the Catalina was an amphibious aircraft, able to operate from land or water. It wasn’t a flying-boat, strictly speaking. The Sunderland remains, in my opinion and that of many experts, the premier military flying-boat of all time.

The Empire flying-boats served Imperial Airways’ needs on the routes heading East from England; but individual stages on those routes were seldom more than 400-500 miles in length. The challenge of the trans-Atlantic routes remained. Two Empire-class flying-boats were lightened and fitted with additional fuel tanks, making them capable of flying the route with a reduced payload, but this wasn’t fully satisfactory. Three different solutions were tried.

The first of these was known as the Short-Mayo Composite, after the company and the designer of the aircraft. A four-engined seaplane, named the Mercury, was mounted on top of a modified S.23 Empire-class flying-boat, named the Maia. The two took off together, using the power of all eight engines to climb to altitude: then the smaller, lighter Mercury separated from the ‘mother ship’ and flew away on its mission, leaving the Maia to return to base. This meant that Mercury could carry a much larger load of fuel than it would be able to lift on its own, making a trans-Atlantic flight entirely feasible.

Here’s a video clip of the trial flights of Mercury and Maia.

Despite the real technical achievements of the program, it was successfully tested only in 1938, during a period of major advances in aviation development. More streamlined aircraft, more powerful engines and other advances meant that larger aircraft could expect to cross the Atlantic safely on their internal fuel. The Maia-Mercury combination would also require expensive ‘carrier’ aircraft at both ends of the route, to lift the ‘passenger’ aircraft with its heavy load of fuel: and this proved to be an uneconomic proposition. Therefore, the concept was not developed into a production model.

A second attempt to conquer the Atlantic with regular air services involved four of the S.30-series Empire boats, which were fitted with in-flight refueling equipment. Three Handley Page HP.54 Harrow bombers of the Royal Air Force were fitted out as tanker aircraft. The idea was for the flying-boats to take off, then take aboard a very large quantity of additional fuel – more than they would have been able to lift from the surface of the water. Laden with fuel, they’d then be able to make the trans-Atlantic crossing successfully. Despite the success of trials, the project was interrupted by the arrival of World War II, which put an end to the experiment.

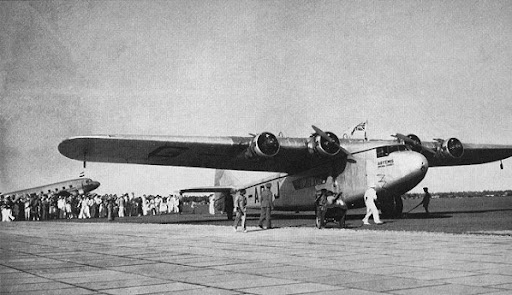

Short also developed the S.26, an enlarged version of the Empire flying-boats, which also used features from the Sunderland military flying-boat. It was designed to have sufficient range and payload to make flying the Atlantic both a practical and an economical proposition. Imperial Airways ordered three, and the first one, named Golden Hind for Sir Francis Drake‘s famous ship, flew in July 1939 – just two months before the outbreak of World War II.

All three S.26’s were taken over for wartime Government service, and two were later used by Imperial Airways’ successor, BOAC. Ironically, tests before and during the war showed that the S.26’s were unnecessary, as the original Empire flying-boats proved capable of carrying enough fuel for trans-Atlantic crossings. Shorts had been extremely conservative in their maximum takeoff weight figures, and when experience showed that these could be exceeded, Empire flying-boats proceeded to make many trans-Atlantic crossings.

The Empire flying-boats enabled Imperial Airways to expand the Empire Air Mail Routes all the way to New Zealand in the East, and to Bermuda in the West. The map below shows the Imperial air mail routes as they eventually existed, prior to and during World War II. The routes marked in red show pre-war services. Those marked in green show the alternate routes developed during World War II, when German occupation closed the European and Mediterranean routes previously used, and Japanese forces rendered those in parts of South-East Asia and the Pacific too dangerous. (Click the map for a larger view.)

The routes are marked in straight lines on the map; but in reality, they curved to follow coastlines, or ran from lake to river to lake across country, so that flying-boats would be as close as possible to convenient bodies of water in case they suffered some malfunction and needed to land. During World War II, when thousands of land-based aircraft were ferried across Africa and through South-East Asia to the war fronts, airports and infrastructure were developed along most of the routes shown.

Needless to say, commercial aviation was taken over by the British government during the war, and BOAC operated at its direction. Services were maintained to many parts of the Empire, but passenger traffic was largely restricted to military personnel being transferred between operational theaters. Mail and urgent strategic materials formed the bulk of the cargo. Many of the Empire flying-boats were lost during the war, some to weather, some to accident, some to enemy action, and some simply disappearing without trace. The long overwater flights necessitated by the new, diverted routes probably took their toll on the overstressed aircraft and engines. For example, the leg from Australia to Sri Lanka stretched over 3,500 miles of ocean, and took a full 17 hours to cross, with no emergency landing facilities available at all. Several aircraft vanished on this route, their fates unknown to this day.

After the end of the war, Shorts produced the Solent flying-boat for BOAC.

However, the spread of infrastructure to support land-based aircraft meant that flying-boats were simply uneconomical on the routes they had formerly dominated. This would spell the end of the flying-boat for commercial use, as they could now be replaced by cheaper, faster and more efficient land-based airplanes. Only 23 Solents were built (or converted from earlier designs), and all had been retired by 1958.

A further death knell for the old Empire Air Mail Route was the rapid spread of national airlines. Increasingly, countries wanted their air mail to be carried aboard their own aircraft, for reasons of national prestige; and with so many former colonies becoming independent, there was no longer so great a need for an official mail network to keep distant officials under control, and allow them to inform the Colonial Secretary of their activities. By the end of the 1950’s the Empire Air Mail Route had ceased to exist as such, and the modern air traffic system had begun to come into being.

It’s worth remembering the courage, drive and sheer determination of the Imperial Airways and BOAC pilots, crews and support staff. They opened up air routes in the face of almost impossible obstacles, often at great personal cost in terms of disease, separation from families for long periods, and the hazards of flying in the less-than-perfectly-reliable aircraft of the day. They were pioneers in the true sense of the world, and they forged the first airborne sinews of empire. It’s not their fault that the Empire was about to implode under the weight of its own tensions, rendering their efforts null and void within a matter of a few decades.

And Shorts? They suffered from the nationalization of most British aviation companies in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The firm produced some useful twin-engined light transports in the 1970’s and 1980’s, as well as manufacturing the Brazilian Tucano training aircraft under license for the RAF. It also developed a series of short-range ground-to-air missiles. Today it’s owned by a Canadian aerospace company, Bombardier, and makes aircraft parts for them. It’s based in Northern Ireland, and is that province’s largest manufacturing concern.

Peter

A fascinating read, Peter. Modern airliners are a very pragmatic solution to the problem of getting from A to B, but doing it in flying boats with lousy nav aids and recalicatrant radial engines makes for much better stories.

Jim

Fantanstic post Peter! I knew about Pan Am, but not about the Shorts. Thanks for a very interesting compilation!

A truly excellent effort, Peter. I'm very glad to see you revisiting your superb Weekend Wings series, and hope you'll continue it as frequently as convenient.

[I'm fully cognizant of the effort needed to research, write, and polish a lengthy and historic article. I'd bet this one was in preparation for, what? A month?]

Anyway, thanks for providing information that I otherwise would likely have missed.

Best,

JPG

The initial BOAC request called for a biplane and it was only at Shorts suggestion that a monoplane be built. Unlike the DC-3, the competition to the Empire boats were not other aircraft or trains but ships so even a slow aircraft was an improvement and comfort was more important than more seats since the passengers would be in the aircraft for a long time.

18 of the Empires survived to be scrapped postwar, despite losses due to enemy aircraft and pilot error, many with between 10 and 15 thousand hours on the airframes.

The choice for using a flying boat had little to do with a lack of reliability but rather to do with fuel. The necessary airfields would have been built had they been required (under the justification of potential RAF use) but when BOAC was costing the run, they discovered that the cost of transporting thousands of tin cans of fuel from the ships that delivered them to the airfields located away from moorages negated the economic advantages of using landplanes. This was partially predicated on the route being broken into fairly short legs and the later removal of many of these stops (with later much faster aircraft) reduced this cost considerably.

The principle handicap seaplanes operate under is not the weight and drag but the surface of the water – if it is either too smooth or too rough, a landing becomes extremely hazardous and at least one Empire boat was lost from smooth water (Coogee), and another (Cavalier) from landing in heavy swells. From what I have read of the internal decisions both BOAC and PanAm moved away from seaplanes because of this problem even more so than the availability of airfields.

I didn't see any mention of the four-engined flying boats which regularly landed on the Zambezi near Livingstone. The local boat club still uses the hard-standing built for the aircraft to launch their boats!