A few personal observations over the past couple of weeks:

- Last Saturday I picked up the tires I ordered a little while ago. They cost me $207.50 apiece, including tax. However, in the two weeks since I placed my order, their retail price had already increased 8%, so I’d have had to pay $896.40 without my pre-order. The tire installer who took my money and loaded the tires into my vehicle told me that by the time I needed to install them (probably in 3-6 months from now), the price would undoubtedly be 20-30% more than today. He said a number of people are doing what I did, ordering and paying for tires now and storing them, rather than wait until the last moment and perhaps not be able to afford the higher price.

- Chicken prices at our local Sams Club have risen by 20% for whole frozen chickens, and 50% across the board for chicken pieces (thighs, breasts, tenderloins, etc.) – in less than one month. Sure, part of that is due to the wholesale slaughter of poultry in an effort to control the current outbreak of bird flu; but even so, if you eat a lot of chicken, that’s a hell of an increase to swallow. (Oddly enough, Sams Club is still selling its rotisserie chickens for $4.98 apiece, but that’s probably a loss leader to attract customers into the store. They can’t be making much of a profit, if any, at that price.)

- I received a warning from the electrical company that recently upgraded our circuit breaker board. I’ve already told them I want them to lead power to our new utility building, which should be ready for that by the end of May. However, they won’t order the necessary parts until a date can be fixed; and apparently the price of the parts is going up almost weekly. With COVID-19 shutting down factories and suspending shipping in China, they may find their regular supply of copper cable, circuit breaker boards and sub-boards, etc. is interrupted or drastically reduced. If I want them to have the parts ready, I’ll have to buy and pay for them now, so they’ll be here when the building is ready. (Needless to say, that’s what I’m doing.)

I’m far from alone in noticing such things. Divemedic comments:

One of the meals that I always make to begin the spring grilling season is: BBQ chicken quarters, grilled ears of yellow corn still in the husk, fries, and grilled watermelon.

I went to Publix to get the stuff today, and [found – see picture at source]:

First, its bicolor corn, not yellow. There is no yellow corn.

Second, bicolor corn is usually even cheaper than yellow.

Third, ears of yellow corn have sold 5 for $2 every spring and summer for the past few years. Until now.

So this is not only a shortage, but also indicates about a 70% year over year increase in the price of corn, and the corn you get for that inflated price is inferior to what you got just a year ago.

Next, I stopped by the meat department for the chicken quarters. They had chicken breasts, they had thighs, and they had breasts, but no quarters. The butcher asked me if I was looking for anything, and I told him I wanted some chicken quarters for some grilling. He laughed and said he was looking for a blonde millionaire who would trade him a Ferrari for some sex. I told him that he must be keeping his Ferrari out back with the chicken quarters. We laughed, but then he said that they have been hard pressed to keep the meat department stocked over the past few weeks.

There’s more at the link.

I was surprised to read of the contribution to food and other costs of the humble wood pallet. The Loadstar reports on the European situation:

The war in Ukraine has claimed a new collateral victim in Europe: the market for wooden pallets – crucial in the packaging, handling and storage of goods.

According to the European Pallet Association. (EPAL), more than 600 million of its pallets and 20m of its box pallets are in circulation.

. . .

“In a few months, the price of a single (new) pallet has risen from €7 to €29 ($7.56 to $31.33). They are increasingly difficult to find and more expensive to produce in a context of soaring raw material costs and in particular the price of wood,” according to La Chaîne Logistique du Froid, a French trade association of 120 companies specialised in the transport and storage of fresh and frozen products, a business vertical that depends on these softwood structures.

. . .

The manufacturing costs of pallets that can be re-used for years rose by an estimated 40% last year and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the end of February has exacerbated the inflationary pressure. Ukraine is a major producer and, before the war, was exporting close to 15m pallets a year to Europe. However, its workshops are now idle, creating a shortage of new products.

In addition, a number of countries in western Europe would, in normal times, source up to 25% of their pallet and packaging wood from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, but conflict and sanctions have brought these supplies to a halt.

Again, more at the link.

If you think the European pallet situation doesn’t affect America, think again – pallets are used to package a great deal of the freight we receive from that continent, so their rising cost directly affects the prices we pay. What’s more, so many pallets are tied up beneath freight that is taking months instead of weeks to deliver, and sitting in warehouses or on trucks or trains or ships far longer than it used to, that manufacturers are being forced to order new pallets, rather than re-use old ones. That’s another added expense, just when the last thing they need is greater input costs. Needless to say, those rising costs are being passed on to us in the retail prices we pay. US pallet prices are rising, too, not because of the Ukraine situation as such, but because of the latter pressures.

An emerging problem is that, as inflation gets worse around the world, it’s destroying demand for many goods and services. Bloomberg reported last month:

Prices for some of the world’s most pivotal products – foods, fuels, plastics, metals – are spiking beyond what many buyers can afford. That’s forcing consumers to cut back and, if the trend grows, may tip economies already buffeted by pandemic and war back into recession.

The phenomenon is happening in ways large and small. Soaring natural gas prices in China force ceramic factories burning the fuel to halve their operations. A Missouri trucking company debates suspending operations because it can’t fully recoup rising diesel costs from customers. European steel mills using electric arc furnaces scale back production as power costs soar, making the metal even more expensive.

Global food prices set a record last month, according to the United Nations, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted shipments from the countries that, together, supply one-quarter of the world’s grain and much of its cooking oil. More-expensive food may be frustrating to the middle class, but it’s devastating to communities trying to claw their way out of poverty. For some, “demand destruction” will be a bloodless way to say “hunger.”

In the developed world, the squeeze between higher energy and food costs could force households to cut discretionary spending – evenings out, vacations, the latest iPhone or PlayStation. China’s decision to put its top steelmaking hub under Covid-19 lockdown could limit supply and push up prices for big-ticket items like home appliances and cars. Electric vehicles from Tesla Inc., Volkswagen AG and General Motors Co. may be the future of transportation, except the lithium in their batteries is almost 500% more expensive than a year ago.

“Altogether, it signals what could turn into a recession,” said Kenneth Medlock III, senior director of the Center for Energy Studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Don’t underestimate the threat this poses to US jobs. If your salary or wage depends on people being willing to buy what your employer produces, what happens to your job if they can no longer afford to buy them? And, if millions more people find themselves out of work as a result, what will that mean for unemployment benefits? Will states and the federal government still be able to afford them when their tax income is crippled through lower economic activity?

(That applies to me, too, of course. My income depends on people not only liking my books, but being able to afford to buy them. If that’s no longer the case, then I guess my emergency food reserves are likely to become my everyday pantry a lot faster than I’d like!)

Our inflation crisis is bad enough as it is, but political manipulation may play a role too.

The Biden administration is desperate to get to June when they can start to cycle through the anniversary of the 2021 inflation spike beginning and start to see annual inflation comparisons level off. The rate of inflation will drop once the statistical year-over-year comparisons reach the same moment in the prior year. The fed will raise interest rates in May and then use the June inflation rate decline as a false talking point to highlight how their policy is working. They wait for May, because they need to wait for the calendar, nothing else. Inflation is measured as the percentage of change from the prior year. By waiting until the inflation is measured against the first wave of rising prices, it will give the illusion of a decline in inflation.

That’s the unspoken background behind Janet Yellen’s statements to CNBC where she says, “We’ll have to put up with inflation a while longer.” It’s all about kicking-the-can until the statistical comparisons lessen, nothing more.

Charles Hugh Smith points out that inflation is exacerbated by debt saturation.

I started writing about debt saturation back in 2011. The basic idea is we can continue to borrow and spend as long as one of two conditions hold: 1) real (inflation-adjusted) income is rising, so there’s more income to service additional debt, or 2) the cost of borrowing declines so the same income can support more debt.

After 13 long years of declining interest rates and stagnant incomes for the bottom 90%, we’ve finally reached debt saturation: after dropping to near-zero, interest rates are now rising, pushing the cost of debt service higher, while wages are losing purchasing power (a.k.a. inflation), so there’s less disposable income left to service debt.

The game plan for the past 13 years was to fund “growth” today by borrowing vast sums from future incomes: the $1.6 trillion in student loan debt, for example, was supposed to be paid by the soaring wages of all those student-loan-serfs, and all the sovereign debt was supposed to be paid by the soaring tax revenues from rapidly expanding economies.

These fantasies have now run aground on the unforgiving shoals of reality. There’s no way to expand debt if income is losing ground and the cost of borrowing is soaring.

In another article, Mr. Smith illustrates how “the global order has cracked. The existing order is breaking down on multiple fronts.“

Under various guises, labels and rationalizations, “free money” has now been established as the default policy fix for any problem. Stock market falters? The solution: free money! Economy falters? The solution: free money! Bankers face collapse from ruinously risky bets? The solution: free money! Infrastructure crumbling? The solution: free money!

Inflation raging? The solution: free money! Ruh-roh. We have a problem free money won’t fix. Instead, free money accelerates the conflagration. Dang, this is inconvenient; the solution to every problem makes this problem worse. Now what do we do?

Despite the apparent surprise of the policy-makers, pundits and apologists, this was common sense. Create trillions of dollars out of thin air and spread the money around indiscriminately (fraudsters and scammers getting more than the honest, of course) after global supply chains were disrupted and shelves were bare, then open the floodgates of speculative gambling in stocks, cryptos, housing, used cars, bat guano, quatloos, etc., and what do you think will happen?

Supply can’t catch up with free-money-boosted demand, prices rise, people instinctively over-order and over-buy, and “don’t fight the Fed” speculative betting begets more betting: the inflation rocket booster ignites, wages soar as workers try to keep pace with rising expenses, speculative bubbles inflate to unprecedented extremes, and all this “wealth without work or productivity” gooses spending and gross domestic product (GDP).

. . .

Alas, all bubbles pop, and now that creating free money only makes costs rise faster, there is no solution other than – oh, dear, dear, dear – the unforgiving discipline of frugality and investing for productivity gains rather than for speculative bubble “wealth.”

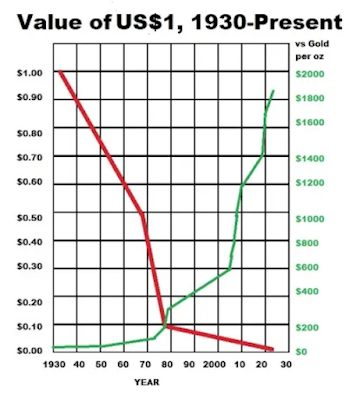

The dilemma is very clearly illustrated by this chart, which I found on Zero Hedge but which has been circulating on many financial Web sites. It illustrates the declining value of the US dollar since 1930, compared to the dollar price of one Troy ounce of gold. Yes, the figures are accurate – I checked them.

The plunge in the value of the dollar can be directly correlated with the number of dollars in circulation. The more dollars there are, the less each one is worth. We call that “inflation” . . . and, with 80% of all US dollars in circulation having been created within the past two years, ain’t we got fun?

Peter

The hole is being dug deeper in big and small ways. A personal example. Chase Bank just increased my Amazon sponsored credit card limit to 25% of my annual income. I'm 77 on social security. Should I max out that card, there is no feasible way I can repay it. I did not request the increase and pay the balance off every month. What rational business model would justify Chase's making the decision to raise anyone's credit limit to 20%+ annual income? Since my other credit cards show up on credit reports, my combined credit limits now exceed my annual income. Insanity! Since my cards have zero balances and will stay that way that may have triggered an automatic increase without any person involved. Still bad business IMO.

When I took Econ 101, we were introduced to a concept called the marginal utility function.

An easy (and common) example is if I give the homeless guy begging on the corner $1, I've made a substantial impact on him while if I give a millionaire $1, I've had virtually no effect on him.

Think about the Fed creating money. They've created trillions and it didn't work. And yet they think creating more will? The marginal utility function implies they'd have to create many times more trillions to matter. Which will collapse the dollar, but I think that's the plan.

One thing to keep an eye on us plywood. Russia is one of the leading exporters of high/furniture grade plywood, especally birch. That supply is gone to spite the Russians.

Russia is one of the few major, global lumber suppliers. The west has decided to cut off the supply.

The pallet issue is an interesting one. Palletized cargo is more visible in breakbulk shipping, especially locally in the Central America- North America foodstuff trade, which is still serviced by traditional reefer ships- ships with refrigerated holds, rather than refrigerated containers… what I don't see are palletized cargo shipped in containers, merely because I don't see inside the containers as I go from ship to ship.

Pallets are more visible in local transportation. At least in the US, we're still moving far too many goods over-the-road than efficiency would dictate because short-sea shipping (use of small coastwise and river-capable ships for interstate commerce) is discouraged due to the present adverse tax environment, not to mention the world's most stringent regulations on domestic shipping. Our over-the-road dependency for stupidly long supply chains is a terrible weakness.

Bird meat? Swallow? I see what you did there.

And there's all those "mysterious" fires and plane crashes at food processing plants recently.

I saw they were charging $1 for each cob of corn, and I told them that was the very definition of piracy – a buck an ear!