As a companion series to my Weekend Wings articles (see links in the sidebar), I’m going to start a Weekend Warships series. This won’t replace Weekend Wings, but I’ll hopefully be able to do more of them, and more often. To do a good Weekend Wings article, with all the references and links, takes me at least twenty hours, sometimes more, and I don’t often have that sort of time to spare. A warship profile will take much less time. I hope you enjoy them.

To start the series, I’d like to focus on the light cruiser USS San Diego (CL-53). (Click the picture below, and most other pictures, for a larger view.)

This remarkable warship steamed over 300,000 miles during World War II, participating in almost every major Pacific campaign from Guadalcanal to the Japanese surrender, and amassed no less than 18 battle stars – more than any other US warship except the famous carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6), which was already in service at the time of Pearl Harbor and garnered a total of 20 battle stars.

San Diego was an Atlanta class light cruiser. Global Security describes the design of the Atlanta class as follows:

This class was intended to replace the 1920s era Omaha class light cruisers. This class was developed to satisfy the need for a light displacement, high speed vessel whose mission was primarily combating large scale attack by aircraft, but which also possessed the ability to perform certain types of cruiser duty. Their initial purpose, contrary to popular belief, was not only that of an anti-aircraft cruiser but that of a small, fast scout cruiser that could operate in conjunction with destroyers on the fringes of the battle line in addition to the defense of the battle line against destroyer and aircraft attack. While they were not designed to “slug it out” with heaver ships, they were well suited to close surface action in bad weather (poor visibility) and to night actions, where their fast firing 5″/38’s and eight 21″ torpedoes could be used to advantage.

The Atlanta class was designed to work with a battle fleet, and consequently had high speed and long range. Their four boilers fed two geared turbines producing 75,000 shaft horsepower, which propelled their 8,340 ton full-load displacement at speeds of up to 32.5 knots (about 37.4 mph, or 60.2 km/h). This compares favorably with the ships they mostly escorted during World War II (the Essex class aircraft carriers, for example, had a maximum speed of 33 knots; the Iowa class battleships normally operated at up to 31 knots, with a dash speed [when lightly loaded] of 35 knots; and the Fletcher class destroyers of the day had a maximum speed of 36.5 knots, although they could not sustain this in heavy weather). The Atlantas had a steeply raked bow, enabling them to keep the seas in severe weather.

The Atlanta class were probably the most heavily gunned light cruisers ever built by any navy. They had no less than 16 5″/38 Mark 12 guns, so called because the barrels were 38 calibers long (i.e. the caliber, 5″, multiplied by 38, producing barrels just under sixteen feet long). They were arranged in eight twin turrets, three forward and three aft along the centerline, with two ‘wing’ turrets, one on either side of and slightly behind the after fire control director. These ‘wing’ turrets normally faced aft during passage, but could sweep from bow to stern on either beam during an engagement.

These rapid-firing main battery guns could deliver a broadside weight of over 17,600 pounds (10,560 kg) of shells per minute, at a rate of up to 22 rounds per barrel per minute for short periods of time (although 12-15 rounds per minute was more usual as a sustained rate of fire). Later ships in the Atlanta class were built without the two wing turrets, reducing their main armament to twelve 5″/38 guns, but the arcs of fire of the turrets were increased to compensate for the lower weight of broadside. San Diego, being one of the first four ships in the class, retained her wing turrets.

A detailed description of the 5″/38 Mark 12 may be found here, and a description of how the turrets were operated (including the very real hazards to gun crews) may be read here.

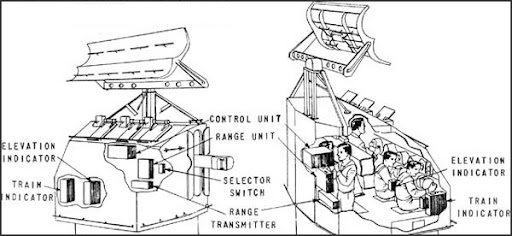

The 5″ guns were directed by twin Mark 37 Gun Fire Control Systems (GFCS). These used dedicated directors, one mounted above the bridge in front of the foremast, the other behind the rear funnel and mast. As first constructed, San Diego lacked radar, so her Mark 37 directors used optical rangefinding equipment to track targets. This was housed in the arms protruding on either side of the director. Later in the war she received fire control radars mounted above the directors, initially Mark 4 radar, later (during an extensive refit in early 1944) the more advanced Mark 12.

The Mark 4 radar had a maximum detection range as follows:

Consolidated PBY Catalina aircraft flying at 5,000 feet: 35,000 yards.

Destroyers: 16,000 yards.

Battleships: 25,000 yards.

In practice, given bad weather and other factors, actual detection ranges were often shorter. Its minimum range was 1,000 yards, inside which the targets could not be tracked due to interference. The later Mark 12 extended detection range slightly, being capable of picking up a Consolidated PBY patrol bomber, flying at 5,000 feet, at up to 40,000 yards. It had a shorter minimum range, and was more powerful, less affected by interference, and could determine range more accurately.

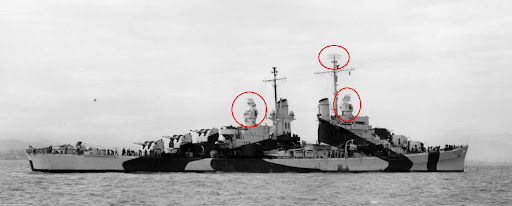

During her refit at Mare Island, near San Francisco, in late 1943 and early 1944, San Diego also received search radar. I haven’t been able to identify precisely what model she received, but the antenna mounted on her foremast closely resembles that of the SC-2 long-wave search radar developed during the middle of the war for destroyers and larger ships. This had a maximum effective range against high-flying aircraft of approximately 70 miles.

In the picture of San Diego below, taken on April 10, 1944 after completion of her refit, the antennae for the Mark 12 radars on each director, and the (presumed) SC-2 search radar antenna on her foremast, are circled in red (click the picture for a larger view).

More information on US Naval radars of World War II may be found here.

San Diego also carried an extensive secondary armament. As commissioned, she was equipped with four quadruple-mount 1.1″ anti-aircraft guns.

These proved unsatisfactory in war service, jamming frequently, and often being ineffective against attacking aircraft. They were replaced as soon as possible on all ships by the 40mm./56 Mark 1 or Mark 2 Bofors cannon, which was probably the best medium-caliber anti-aircraft gun of the entire war. San Diego received 16 of the Bofors cannon in four quadruple mounts to replace her 1.1″ weapons.

As commissioned, San Diego also carried six 20mm./70 Oerlikon light anti-aircraft guns in single mounts. This was later increased to an ‘official’ total of 13 such weapons, which were squeezed into any available space in single or double mounts. Various reports indicate that as many as 20 Oerlikons may have been shoehorned into San Diego, some ‘unofficially’ obtained (in the finest traditions of combat sailors, who throughout history have seldom let bureaucratic limitations or supply difficulties stand in their way if something is critical to their comfort or safety).

The Oerlikons were reasonably effective against aircraft attacking in a conventional manner (i.e. dropping bombs or torpedoes, or strafing with machine-guns), but proved inadequate to stop later kamikaze attacks. During the latter, the aircraft pilot was intent on crashing into the ship, and minor damage would seldom stop him. Only major damage to or complete destruction of the aircraft would suffice, and to ensure this a larger caliber weapon with greater explosive power was required. Plans were afoot to replace some 20mm. guns with single air-cooled 40mm. Bofors cannon when the end of the war rendered them unnecessary.

San Diego also carried eight 21″ torpedo tubes in twin quadruple mounts, as well as depth charge rails and launchers, and sonar to direct the latter. Neither torpedoes nor depth-charges were never used in combat; indeed, the latter proved to be a liability in that they made the ship’s fantail excessively crowded during combat operations. In the photograph below, taken on April 9, 1944 during her refit at Mare Island, San Diego‘s depth-charges can be seen on her stern, behind her aftermost 40mm./56 Bofors quadruple mount.

The torpedoes and depth charges were, of course, intended for use if San Diego had served in her designed role as a scout cruiser to protect the Fleet. However, her war service was almost exclusively spent providing anti-aircraft cover to the aircraft carriers of the Fleet, so any weapons not needed for that job were superfluous. Her three spotter planes weren’t needed to scout for the Fleet, as designed: however, they directed her guns during shore bombardments in various campaigns.

To operate all these weapons and her powerful machinery, San Diego‘s official complement was 796 officers and enlisted men. By the end of World War II, with the demands of her added guns and equipment, she embarked over 850 personnel, according to one account, which made her living spaces rather crowded. At the end of the war, while repatriating personnel from Japan, she reportedly embarked 250 passengers over and above her complement, which must have been a very tight squeeze indeed for everyone aboard!

San Diego was one of the busiest warships in the US Navy for almost the entire war. She arrived in the Pacific just too late to participate in the Battle of Midway in mid-1942, but thereafter served in almost every major campaign of the Pacific War. The USS San Diego Memorial Association Web site sums up her career as follows.

On August 12 [1945], Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, colorful commander of the huge United States Third Fleet, sent a message to a light cruiser, the USS SAN DIEGO (CL 53), as follows: “SAN DIEGO designated as flagship for Commander Task Force 31, and thus in the center of all activity. Seeing an imminent end of combat, Halsey handpicked the SAN DIEGO to be the first major warship to enter Tokyo Bay once the enemy surrendered unconditionally. That event happened two days later, on August 14, signaling the end to the long and vicious fighting that started with the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

The crew of the SAN DIEGO felt that they had rightfully earned the honor with a remarkable wartime record. She’d won 18 battle stars. She took part in 34 major battle actions; steamed an incredible 300,000 miles at sea with only short stops at such out-of-the-way places as Majuro, Eniwetok and Ulithi atolls; and never took a direct hit or lost a man in combat from the day she was commissioned in January’ 1942. Bob Alderson, yeoman third class, attributed the success of the SAN DIEGO to his shipmates. He said, “I think it was the accuracy of our aim. The more our ship was in battle, the greater our chances of survival because we knew what we were doing. We had complete confidence and good skippers.”

Then there was the design of SAN DIEGO, which made life a nightmare for the enemy aviators. As one officer observed, “When seven turrets with fourteen five-inch guns were all firing at the enemy, it looked like the ship itself was on fire.”

. . .

The saga of the SAN DIEGO dates back to 1938 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a large appropriations bill to build new warships. The President believed what few did then, that Adolph Hitler was building a powerful armed force preparing to go to war against the Atlantic alliance, a conflict we could not avoid.

A strong contingent of energetic San Diegans went to Washington to support rebuilding the Navy, and to persuade the President to name a new cruiser after the city of San Diego. They were successful.

The keel was laid in March, 1940, for the new cruiser USS SAN DIEGO (CL 53) at the Bethlehem Steel Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was the third of eight of a new design that came to be known as the Atlanta Class, essentially constructed to produce heavy anti-aircraft fire from eight twin five inch 38 caliber gun mounts, along with many secondary machine guns. She had a three and a half-inch armor belt, with two inches of deck armor. The three tiered mounts forward and aft gave her a beautiful silhouette.

In July, 1941, the San Diego sponsoring group went to Quincy to take part in the christening and launching festivities. Mrs. Grace Benbough, wife of Mayor Percy Benbough, splashed the champagne for the launching. San Diego Chamber of Commerce members and other dignitaries attended.

The ship fitted out at the Boston Navy Yard, and about a month after Pearl Harbor the SAN DIEGO was commissioned on January 10, 1942. It was snowing, and the weather was cold and miserable, perhaps a portent of the tough year ahead. A nucleus crew of officers and senior crewmen had been assigned months prior to the completion of the ship. The full complement of 650 men arrived on commissioning day, consisting largely of graduate recruits from boot camp and reserve officers, to supplement the experienced regular Navy petty officers and Naval Academy-trained officers.

The ship’s Commanding Officer, Captain Benjamin Franklin Perry, commendably was a man of few but measured words. In the subzero temperature and eight inches of snow, Captain Perry said, “This ship will be an honor to the city of San Diego. The time for talk is over; let’s get going.” The executive officer was Commander Timothy O’Brien, who later made admiral.

The new light cruiser was 541 feet in length with a beam of 53 ft. Her full load displacement was 7,500 tons. She was destined to build a formidable record and set a high example for her seven sister ships.

SAN DIEGO went through a condensed shakedown and training period in the Portland, Maine, area. She then headed for the Panama Canal, en route to her namesake city for special training before heading, out to the Pacific combat zone.

From day one of the War, a cloak of secrecy surrounded all ship and personnel movements. Nearly everyone in the city of San Diego was unaware that her namesake had arrived in port on May 17, 1942. While the training exercises continued until the end of May, the crew took every opportunity for liberty when in port. One anonymous young fireman from the engineering department went on a royal “toot”. At length, he encountered a local policeman who noticed his instability. As the hour was late the policeman asked, “Where are you from, sailor?” The sailor: “SAN DIEGO.” Policeman: “What part of San Diego?” Sailor: “The forward boiler room.” The policeman led the sailor off to the drying-out tank, having never heard of a ship with that name.

The ship’s disbursing officer (paymaster), Ensign Len Shea, had handled millions of dollars with great integrity throughout his regular Navy career. But finding himself a bit shy on funds while ashore on liberty, he sauntered into a bank to cash a check. His uniform said he was in the Navy but when the cautious teller asked what ship he was on Ensign Shea stalled a bit before finally revealing the name “SAN DIEGO.” The teller rather sourly said, “Get outa here! There’s no ship named SAN DIEGO.” (The former paymaster retired as captain, and lives in Coronado.)

Two weeks later, on June 1, 1942, the ship departed San Diego. (It would be 41 months before the city and the USS SAN DIEGO would get together again, and that for a huge postwar victory jamboree.)

The ship escorted the SARATOGA, a large carrier, to Pearl Harbor. Further training, exercises over four weeks brought the feeling of war closer, until in mid-August the SAN DIEGO got underway as part of Task Force 17 escorting carriers and tankers to the battle area in the southwest Pacific. She arrived a week after the tragic Battle of Savo Island.

For 41 days the ship was at sea supporting the Marines’ invasion of Guadalcanal. Fierce fighting called for periodic reinforcements for both the Marines and the Japanese. While on patrol off Guadalcanal, the ship’s crew saw the carrier WASP sunk by torpedoes from a Japanese submarine, which also damaged the destroyer O’BRIEN and the battleship NORTH CAROLINA.

Toward the end of September, Task Force 17, headed up by Rear Admiral George D. Murray, sailed into Noumea, New Caledonia. After provisioning in four days, they set out to sea for what proved to be the first action of the War for the SAN DIEGO. A raid on enemy islands Buin and Faisi earned the ship her first battle star.

At the end of October came the Battle of Santa Cruz Island, considered by the crew as the first major action of their careers. American naval forces were beginning to threaten Japan’s control of the sea and the air around Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands. The enemy mounted a large force of carriers and heavy ships to wipe out the threat. The SAN DIEGO was stationed to protect the port side of the valiant USS HORNET which had been bombed and torpedoed on the starboard side. The carrier could not be saved, but the SAN DIEGO took off 200 survivors. Her five-inch guns were credited with bringing down three planes. Gunner’s mate Tom Kane, manning a 20 millimeter machine gun on the aft end of the ship, shot down a torpedo plane directly astern. The gunnery officer, Lieutenant Commander Brooke Schunim, witnessed and confirmed the kill. (For 30 years after the war, Kane was a writer for actor John Wayne.)

The enemy, failing to unload a large contingent of infantry reinforcements, suffered three damaged cruisers, a wounded battleship and 123 planes knocked down, and then withdrew from the fray as did the enemy troop ships. The SAN DIEGO survived without casualties or real damage, and won its second battle star. Santa Cruz was decisive because the expansion of Japan’s power was stopped cold by a US force whose warships were outnumbered 46 enemy ships to 33 of ours.

Nearly everyone on board the SAN DIEGO remembers well the days their task force spent near Guadalcanal at night. An enemy twin-engined plane, nicknamed “Washing Machine Charley,” flew over nearly every night. His engines were out of synchronization, and made a loud, annoying noise, enough to keep everyone awake. He’d drop a few bombs but never hit anyone.

Many of the crew recalled tying up alongside anchored sister ship SAN JUAN, in one of several atolls. In the evening, while awaiting movies on the fantail, a potato fight would break out between ships, amid hearty insults flying back and forth. That would bring some officers roaring back to the fantail to halt “the disrespectful treatment of Navy food.” Entertainment was difficult to come by.

November 1942 found the enemy making a last desperate attempt to reinforce their beleaguered troops and regain control of the Island and Henderson Field. At the conclusion of the decisive Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, all 11 Japanese troop ships involved were destroyed – either sunk or beached – with an estimated 24,000 personnel losses. This time the SAN DIEGO was with the carrier ENTERPRISE, whose planes helped demolish the reinforcement effort. The action earned the light cruiser another battle star.

Early in February 1943, the Japanese frantically sent 20 destroyers at high speed “down the Slot” to Guadalcanal. It appeared to be still another reinforcement action, but was, in fact, a clever evacuation of 11,000 enemy troops, which Admiral Nimitz praised. That ended the Guadalcanal stalemate. From then on, the American forces took the offensive that led to Tokyo, as a relentless flow of new ships and planes established superiority over a weakening enemy. The SAN DIEGO survived the darkest days, fighting in nearly every battle to finally turn the tide.

Over the next six months or so, the SAN DIEGO operated in and around Espiritu Santo and Noumea, either on patrol or on exercises, with one large interlude. On March 14, the ship got underway bright and early. At 0600, Captain Perry announced over the public address system that “this ship is underway for Auckland, New Zealand, for about a 12-day stay. We will steam at 26 knots.” It was an electrifying message. New Zealand was a dream place for liberty, dining and friendliness.

Auckland was magnificent, as were such treats as fresh milk, fresh vegetables and excellent waitress service. (Americans tipped handsomely, contrary to Kiwi practices). The crew favored the nightlife at the Peter Pan Ballroom, especially the New Zealand girls from 15 to 50 who mobbed the place. During their stay, a special national holiday festival was held to honor the Maori natives. Prime Minister Peter Fraser and the King and Queen of the Maori tribe attended. Seventy-five sailors from the ship were invited. Some hostesses were present, but most of the sailors arranged their own dates. What a highlight!

On March 19, Captain Perry was relieved of command by Captain J. L. Hudson. Under the firm leadership of Captain Perry, SAN DIEGO had established a solid reputation for being dependable and always ready to go. He’d fashioned a fine ship while earning the first four of eighteen battle stars.

Except for 30 days from the end of June, when the SAN DIEGO joined Task Force 14 to provide support for the successful invasion of Munda, a British protectorate in the Solomon Islands, the ship sailed mostly in and around New Hebrides and New Caledonia. Bill Butcher, a gunner’s mate second class, recalled that before arriving in New Hebrides someone removed some water from a flask on a life raft and replaced it with some raisins. With the normal motions of the ship at sea, the flask got quite a shaking, so much so that when the ship entered port in New Hebrides, it blew up. Since there were many mines in those waters, some sailors celebrated, thinking the ship had taken a hit, and would be heading home.

Starting in November, SAN DIEGO and her “playmates” were assigned to the Central Pacific theater, joining the Third Fleet, which became the Fifth Fleet by a flick of the numbers. Many new ships were steadily arriving and the task forces were burgeoning into powerful groups.

In November, the SAN DIEGO participated in two raids on the Japanese strong -hold base of Rabaul (another battle star) followed by the invasion and capture of the Gilbert Islands (still another battle star).

With her sister ship SAN JUAN, SAN DIEGO was dispatched to Mare Island in December for more extensive yard work. The weather en route was pretty rough. Cliff Rayl, seaman first class, (now retired in California) was assigned a bunk directly below five inch twin gun mount number eight. While the ship tossed about in the rough seas, he and four shipmates were enjoying a friendly poker game. For a card table they were using the closed hatch to the ammunition magazine below; the hatch to the gun mount above was open for ventilation. On one bad roll, a five-inch shell broke loose, and fell down the hatch. It landed on their “card table” with a live nose fuse. An alert sailor picked up the shell, rushed it topside and threw it overboard. That wasn’t the end to their troubles.

Two new four-bladed propellers that had been welded and chained to the deck for transit to the States started to come loose in heavy seas. In the dark of night, deck hands were summoned topside to secure them. The decks were awash. Coxswain George Horton was hit by a wave coming over the port side that carried him through the lifelines. Just as it looked like he was a “goner” he was able to grab the middle guard line, when another wave washed him back on board.

In November came the gigantic typhoon that was the most violent anyone had encountered. The wind speed rose rapidly to over 100 mph. SAN DIEGO took rolls of 37 degrees then 45 degrees, then 50 degrees. A huge wave came over her amidships, tore the #1 motor whaleboat off the davits and sent it reeling into the superstructure, smashing it in two. Three men were injured when five-inch ammunition came loose and bashed them. Over 120 planes on board the carriers were wrecked by the fierce storm. Three destroyers capsized, they had been light on fuel and hadn’t sufficient ballast. A dozen other ships were damaged. It took four days for this worst of typhoons to fade, and was the most frightening, vicious storm in memory.

About mid-December Lieutenant Commander Joe Eliot, the gunnery officer, put out a special notice about a threat worse than typhoons – kamikaze attacks.”‘ More and more, the Japanese kamikaze tactic was seen as the last possible hope for Japan’s badly decimated air arm. These suicide missions caused tremendous damage to over one-hundred ships. The gunnery officer set about training gun crews to fire the guns manually, in case all electrical power was lost. It wasn’t much fun. But it paid off.

The Third Fleet became the Fifth Fleet in the first part of February, 1945 as the same ships in the same groups took off to support the invasion of Iwo Jima. As March came in, the SAN DIEGO joined Rear Admiral F. E. M. Whiting with VINCENNES (CA 44), MIAMI (CL 89) and Destroyer Squadron 61 for a shore bombardment of Okino Daito (or Borodino) Island, 195 miles east of Okinawa. The force made three firing runs on a reported enemy radar station there.

In mid-March, and for the next two months, life for the SAN DIEGO crew was an endless schedule of sorties to support invasion landings in the Okinawa area. The one important diversion involved towing and escorting the USS HAGGARD (DD 555), a destroyer that was terribly damaged by a kamikaze.

USS San Diego approaches USS Haggard after the latter was damaged by a kamikaze.The SAN DIEGO took off 31 of the badly wounded while en route to Kerama Retto, a protected island repair base off Okinawa. The crew turned from fighting to tending the sick, giving up their bunks to the seriously wounded. They provided food, candy, ice cream; new uniforms and comfort. A few days later, the survivors were transferred to a hospital ship, and the SAN DIEGO rejoined its formation.

At the end of May, another switch in fleet numbers put everyone back in the Third Fleet, in support of the Okinawa campaign. Admiral Halsey commanded the Third Fleet, Admiral Spruance the Fifth.

For two days at the end of June, the ship was dry docked in the Philippines for minor repairs, a routine inspection of her bottom, and rest for the crew. In mid-July, SAN DIEGO skipper Captain William Mullan passed word to the crew that the ship would be going back to the States for a yard availability, or maintenance period, in mid-August. The crew exploded with joy. At the end of three years in the combat zone without a full overhaul, the ship and crew deserved a little relief. However, it was not to be: such are the Navy’s ways. The U.S. forces began massive and incessant B-29 bombing attacks and shore bombardment of the Japanese seacoasts by powerful naval forces -aggressive preparations for the invasion of Japan. SAN DIEGO was ordered back to operate with the Third Fleet through July into early August, when Admiral Halsey sent all fleet units to rendezvous 200 miles east of Tokyo. But two atomic bomb blasts virtually ended the War, and the Japanese Finally surrendered unconditionally in mid-August.

The climax of SAN DIEGO’s war career was her selection to be flagship of Task Force 31. With her dramatic entry into Tokyo Bay, the United States accepted the surrender of the giant Yokosuka Naval Shipyard. The ship had been winning battle stars right up until September 2, when, weary of the great long battle, she headed for home, having thereby earned the Japanese Occupation Medal as well.

USS San Diego docks in Yokosuka, Japan, August 1945, becoming the first Allied warship to dock in Japan at the end of World War IIOn the last of the three days they were docked in the Yokosuka Naval Shipyard, all of the SAN DIEGO’s crew were allowed to set foot in Japan. One clever sailor put it, “It was like thirty seconds over Yokosuka,” but everyone was proud to be number one.

On September 1, they pulled away from the dock to anchor a short distance offshore, where they took aboard 250 officers and men as passengers. They were fully qualified for discharge and were eligible to go home. The following, morning, SAN DIEGO pulled her hook out of the Tokyo Bay mud and steamed out at 27 knots on a direct course for home – San Francisco. That same day, the formal surrender by Japan took place aboard the USS MISSOURI, as 258 allied ships filled the bay to celebrate their victory.

From the SAN DIEGO’s cruise book: “Anchoring in Tokyo Bay will be remembered for two things. We saw a real setting sun over Fujiyama, and we had movies on the fantail. If we needed any last assurance that the war was over that was it.”

San Francisco gave a giant welcome to the decorated ship passing under the Golden Gate upon arrival in the USA. The city of San Diego then invited the USS SAN DIEGO to a much larger celebration on Navy Day, October 27th, the most extravagant bash the city ever hosted.

USS San Diego returns to her namesake port in October 1945Chief electrician’s mate Mike Lawless, of the Navy Veterans Association, composed this tribute; “Of all the ships and all the crews I served with the U.S.S. San Diego, CL-53 and crew has a special place in my heart. It always has and always will be my favorite ship and crew. The day I left the San Diego CL-53, I walked from the gangway to the bow with my seabag slung over my shoulder, and I said to myself, I am just going to keep walking and not look back. When I was parallel to the bow, I stopped, took a look back at that beautiful ship and said, ‘You carried me all through that war safely and brought me back,’ then I proceeded to cry like a baby.”

USS San Diego was, by all available accounts, a happy ship and a very fortunate one. She made it through no less than 34 separate combat actions without suffering damage or casualties, while rendering sterling service in the defense of the carrier battle fleet. How many Japanese aircraft she damaged and/or shot down will never be precisely known, but it’s been estimated in the low three figures.

The cruiser was scrapped in 1959, but a new USS San Diego, LPD 22, is currently taking shape. This one’s a San Antonio class amphibious transport dock ship, which is due to be launched later this year and commissioned in 2011.

She’ll have big shoes to fill, given the reputation of her predecessor.

Peter

Thank you for putting this together! The new ship has big shoes to fill, indeed.

Jim

Great post Peter! Thanks for the time and effort!

Pedro – – –

WELL DONE, sir! This was a great start for your Weekend Warships series, and I'll look forward tro more. I've been an aviation enthusiast since childhood, so the Weekend Wings articles will remain my favorites – – after the shooting stuff – -, but I'm always amenable to expanding my horizons.

JPG

Wonderful post! My Father and his Brother served on ships in the Pacific in the War. My Uncle was on a cruiser sunk by Kamakazie attack and had to swim ashore. I think that was at Okinawa. My future Father in law was on shore with the Army as a Machine gunner with the Corps of Eng battalian.

Peter, Outstanding, and thank you.

Bravo Zulu. I was "shipmates" with the venerable 5"/38 gunmounts (they are technically NOT turrets) when I was recommissioning Weapons Officer in USS IOWA in 1984. The Iowa-class battleships originally had ten of these mounts, but the number was reduced to six to help make way for the missile systems added in the newest modernization. Even with only three twin-gun mounts firing per side, they put out an awsome amount of noise and fir balls. I can only imagine the firepower of seven of these gunmounts inaction off the side of the San Diego. Sadly, these old antiques were really obsolete, and the MK 25 radars in their MK37 directors (of which we had four) were pretty much useless in the last commission of these four battleships, but they looked mean.

Peter,

Thanks for this post on the San Diego. As a model ship builder, I have always visually admired the San Diego class of cruisers, the long sweeping curve of their hulls certainly gives meaning to the term "she" that has long been applied to ships. Your post and pictures give her the personality, and is a terrific tribute to not only the ship, but the men who served aboard her.

Well done sir!

Joe Dunlap

My father James E. Brown was an Annapolis grad aboard the San Diego from August 1943 till the war ended. He relayed this story to his sons: "I may have been the only officer who ever waved off a four star admiral's launch!" Apparently he was OOD at the Yokasuka mooring as Admiral Halsey's launch approached for an important preliminary meeting regarding the surrender scheduled on the Battleship Missouri. As Halseys' launch prepared to moor alongside flagship San Diego, Admiral Nimitzs' launch appeared. Protocol had Dad waving off the four star Admiral in deference to the five star!

So proud to see my grandfather Brooke Schumm mentioned in this article. He was later captain of the USS Salem and eventually an admiral in the navy. Sincerely, Julie Schumm Klein